books: books bothfleshandnot davidfosterwallace dfw federer review

by mattbucher

2 comments

D.F. Wallace Both Flesh and Not

Like many others, I greet the publication of this collection of nonfiction pieces, Both Flesh and Not, by David Foster Wallace, with a little bit of trepidation. For one, I’ve read all this stuff already. Granted, I am a devoted fan of DFW’s, but I’d reckon that almost every fan of his has read either the Federer essay or his Salon.com list of under-appreciated novels or one of the other shorter pieces in this collection for free, online. So that’s a little disappointing. There’s nothing here previously unpublished or expanded or gleaned from his recently opened archives at the Harry Ransom Center. But I am glad this book exists and that it pours into concrete book-form some of Wallace’s lesser-known essays.

The title piece, “Federer Both Flesh and Not” (from which the book sorta takes its title) was published in the New York Times “Play” magazine under the title “Federer as Religious Experience.” The version here is exactly the same as that published in the New York Times. Wallace’s editor at “Play,” Josh Dean, writes about “how much [Wallace] cared about every single letter in an 11,000-word story” and then later quotes a letter from Wallace saying “I’ve got the fucker down to like 8,400 words. Another maybe 100-200 words can come out without much problem, if need be. Cutting much more from that will cripple the piece, which I’ve worked hard on and feel protective of. (If you decided, for instance, that you want to run only like 5,000 words of it, I wouldn’t do it — I’d settle for the Kill Fee.†And then we learn: “Another 100 or so words were trimmed for space, and the piece ran as Play’s cover story on August 20, 2006.” My question is: why not give us the 11,000 word version here in the book? Maybe we’d get to see more of the “religious” storyline or more rococo detail about Federer’s beautiful moves (“Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip”). Why not restore it all when you are not bound by the strict printed-word limits of the New York Times? I don’t get it.

Roger Federer has been directly asked about this piece several times and he’s said he admires the piece. Here he is 2009 when asked about it:

Q. There were times during your match today when I was reminded of an essay by the late American author, David Foster Wallace. It’s called “Roger Federer as Religious Experience.” I’m wondering if you have heard of this essay, read it, or what you think of it?

ROGER FEDERER: Sure, I remember his piece. I remember doing the interview here on the grounds, up on the grass. I had a funny feeling walking out of the interview. I wasn’t sure what was going to come out of it, because I didn’t know exactly what direction he was going to go. The piece was obviously fantastic. You know, yeah, it’s completely different to what I’ve read in the past about me anyway.

But one of his joking comments caused a minor stir. The Italian paper La Stampa published an interview with Federer in September 2009:

Foster Wallace wrote that seeing Federer play was like a religious experience.

I did an interview with him at Wimbledon for half an hour, one of the strangest I’ve ever done. As I was leaving I was still wondering what we had talked about. I was very [stricken]* by his suicide.

Have you any idea about that?

I hope, I’m sure it was not because of me. … Artists like him have high level ideals, which often do not hold up, unfortunately, the confrontation with life. He wrote a wonderful essay about me. Thanks to him, also, the world is a better place for me.

That “stricken” [molto colpito] could also be interpreted as “impressed” or “affected”, (it’s not clear what language the interview was conducted in before it was translated into Italian) but the hint that Wallace’s suicide “was not because of me” seems odd here because in the context of the interview, it feels like it’s Federer’s way of pointing up what an absurd question it is for him to comment on, and yet Federer still manages to append a couple of genuinely heartfelt and eloquent sentences after that moment. Still, some fools tried to connect Federer’s decline (or Sarah Palin’s nomination) with Wallace’s suicide and Sports Illustrated’s tennis writer was asked about the comments to the point that he had to clarify “Just to put this rest, I’m sure Federer was right: He did not trigger Wallace’s suicide.” That said, at the 2012 New Yorker Festival in October, Mark Costello made the point that, before his death, Wallace just “couldn’t write anymore” and that the Federer piece “was the last time that his ass left the chair”, meaning that Wallace was so inspired while writing it that he no longer felt his ass in the chair. So maybe it’s not entirely fair to say that there is no connection at all between this essay on Federer and Wallace’s own decline.

Unless you read the flap copy, there is no indication from the front or back cover that this book contains the seminal essay about Roger Federer—and one of the best extant essays about contemporary tennis, period. (There is a standalone Italian edition. DFW is very big in Italy. And there is an illustrated version.) I don’t know how many other reviewers will be compelled to draw comparisons between Federer and Wallace—the best essayist writing about the best tennis player. Of course the title of “best” is subjective and only grudgingly granted, and always fleeting. Wallace is gone, Nadal and Djokovic have surpassed Federer (though, at this very moment, Federer is back atop the ATP rankings {or near the top, it changes frequently}). Wallace claims that seeing Federer play live at Wimbledon is a “near-religious experience.” Even then, he has to qualify it with near.”

Of course, this insight is nothing new. Sublime victory on the playing field has been compared to religious ecstasy thousands of time before (just ask Yankees fans). However, the narrative of Federer winning Wimbledon was not thrilling or ecstatic so much as routine (in 2006, at least) so what Wallace is talking about in terms of “religious experience” is something else, something related to the beauty of an athlete who is able to routinely use his body to do the seemingly impossible. This resembles the beauty of Wallace’s writing to me: something bound not by a thrilling narrative or personality, but the depth of action between the baselines of the page.

“Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young” is an important essay about a group of fiction writers who all emerged around the same time in the early 1980s. He wrote this essay in the Fall of 1987 after he’d submitted his MFA thesis and taken a short-term gig teaching at his alma mater, Amherst.

“Back in New Fire” is a piece that DFW probably never collected because the argument, even couched in “ifs” and “but so then”, could sound completely hideous: AIDS is a blessing?? The piece first appeared in Dave Eggers’ Might magazine under the title “Impediments to Passion” and was collected in the Might anthology, Shiny Adidas Track Suits and the Death of Camp, under the title “Hail the Returning Dragon, Clothed in New Fire.” Not sure where the title “Back in New Fire” comes from, but it isn’t Wallace’s.

http://www.theknowe.net/dfwfiles/pdfs/Wallace-Hail_the_Returning_Dragon.pdf

I have this very slight notion that Wallace got the idea for this piece while he was in the halfway house in Boston. One bit in support of that idea is this remembrance by a fellow AA member in Bloomington, IL:

Dave shared a story once with ”there was a newcomer in a meeting no, I think somebody had come back from a relapse. And he shared this story about when he was in the halfway house. And he said they always had like these people that’d come in and they would kind of educate you about some life skills. And this person talked about the AIDS virus and how it lives in very dark places, dark, damp places. And that it’s not airborne. And he made the relationship for the newcomer about alcoholism. And that once you talk about it, it loses its power over you. Once you talk about what’s going on, it loses its power. And that person just lit up with this confidence that they could, you know, stay sober, they could do this. He was very generous with sharing his experience with people, his struggles, and I don’t know.

Jay Jennings, the former editor of Tennis Magazine, who in 1996 commissioned Wallace to write an article about the U.S. Open (“Democracy and Commerce at the U.S. Open”), donated the page proofs of that essay to the Ransom Center’s collection.

Wallace’s reviews of Borges: A Life and The Best American Prose Poem are excellent, but I really wish that this collection had included even more pieces (see Ryan Niman’s excellent bibliography at The Knowe for the most complete list of Wallace’s unpublished or uncollected nonfiction). I mean, if you are going to go all out and collect the stuff then why leave out Wallace’s early book reviews (of Clive Barker’s Great and Secret Show, J.G. Ballard’s War Fever, Dead Elvis by Greil Marcus, and others). Also missing is Wallace’s introduction, titled Quo Vadis, to the issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction that he guest edited. That piece includes gems like this:

I have observed in myself a kind of sine-wavelike cycle of interest and boredom and interest in riding herd on a project like this. In a way, it’s sort of like my cycle of feelings about religion. To me, religion is incredibly fascinating as a general abstract object of thought—it might be the most interesting thing there is. But when it gets to the point of trying to communicate specific or persuasive stuff about religion, I find I always get frustrated or bored.

Or it would be nice to see the long contributor’s note he drafted for the Best American Short Stories 1992. These omissions just open the door for another (albeit slim) volume to be published later.

The lists of words that run between essays are nice, but don’t add much in this context. I’d rather see just a reprint of the list of words without the definitions or maybe a nice reproduction of one of the handwritten pages housed in the Ransom Center. One neat addendum to this book is this ad, which ran in the same issue of Rain Taxi as Wallace’s review of The Best American Prose Poem, and includes his blurb for Davis’s book (“Probably well worth checking out”) and the small-type disclaimer: “Paid for by the reviewer of The Best American Prose Poem: An International Journal.”

If you are a collector of all-things-DFW, you probably ordered this book and have already reread it (since you likely read the contents of it long ago). You will remove it from its box, turn it over, glance at it, and kindly shelve it in the Ws. If you love tennis and/or beautiful sentences, you need to stop and read “Federer Both Flesh and Not.”

The Art of Fielding

UPDATE: I wrote this little review like a year ago and didn’t publish it because I was not thrilled with Harbach’s book. The reasons for not liking the book were fairly elusive, though, because I did read the whole thing and didn’t fling it out the window or anything. I was trying to find something positive to say about the novel, and well, the positives just didn’t add up to much. I would be interested in other perspectives.

Chad Harbach’s novel The Art of Fielding appears this month [Oct 2011] from Little, Brown. In the Kindle Single documenting the path-to-publication of the novel, Keith Gessen reminds us that Harbach’s publisher and editor are also the publisher and editor of David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest (Little, Brown and Michael Pietsch). Although the blurb on the front (and back!) cover make it clear that this is more Franzen territory than another DFW imitator, there are a couple of similarities: the tennis academy/baseball college and the gravedigging.

The most obvious influence on The Art of Fielding, however is Moby-Dick. There are a lot of times where Harbach does all but say “it’s like in Moby-Dick how…” or “Starbuck…sorry, I mean Starblind,” but I don’t mean to chalk this up as a negative. There is a big reading audience out there for novels about college, baseball, and Moby-Dick, and I fit in there, too.

The novel does a good job of showing us the inner lives of these college boys without veering off into a celebration of “bro” culture. [There is even a special term for two bros on the same baseball team who do everything together a la Schwartzy and Skrimshander: basebromance.] Harbach sets himself up with some stereotypes that he must somehow surpass–and for the most part he does.

Harbach paints a convincing portrait of Skrimshander and Schwartzy (and even Affenlight), but Pella remains an enigma—the damsel in distress, discovering herself again, falling for the wrong guy, a walking cliché; it gets harder and harder to visualize her as a real person in this otherwise-convincing reality drama.

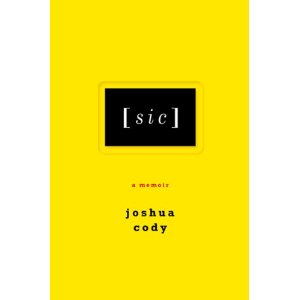

[sic] by Joshua Cody

Joshua Cody’s new memoir [sic] is partly the story of how he—a young man living in New York City, a composer, a descendant of Buffalo Bill Cody—was diagnosed with cancer (a lymphoma of some sort, he never really says) and the treatment didn’t work and he had to get a bone marrow transplant, but really it’s mostly the story of what it’s like to be inside Joshua Cody’s head. One thing fiction (and memoir) teaches us, one of its greatest assets is that it’s possible (and good) to think beyond our selves—to actively try to adopt another’s point of view. David Foster Wallace says it way better than me: “I guess a big part of serious fiction’s purpose is to give the reader, who like all of us is sort of marooned in her own skull, to give her imaginative access to other selves.†And then in the same breath Wallace goes on to explain some of the same stuff about suffering that Joshua Cody is dealing with in [sic]:

Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience, more like a sort of “generalization†of suffering. Does this make sense? We all suffer alone in the real world; true empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside. It might just be that simple.

But we’re getting a little ahead of our selves here. Both Wallace and Cody struggle with knowing something long and complex and looking at it, think “How do I tell this story? Where do you begin? How about this little bit here? Is that really the beginning? Bear with me while I go back and explain…†This struggle to deal with narrative and the flow of the story/plot reflects a lifelong struggle to live in a way that is not constantly fracturing and forking off in different directions. But that does not mean the story and the life are formless. Cody is a trained composer, a musician. He is deeply concerned about form and framing.

Cody is clearly a David Foster Wallace fan—and Wallace’s struggle with depression and eventual suicide haunt him. “Our greatest writer. As if I wasn’t thinking of him during that whole thing. My God. As if he hadn’t helped.” Cody contemplates killing himself (in a scene reminiscent of The Royal Tenenbaums), standing in front of a mirror, well actually “it was me between two mirrors, producing an infinite line of selves, like at the end of Citizen Kane.” And the crucial question he finds before him is: “How do we position suffering in human life?” And this is where it gets interesting, because maybe we think of a cancer memoir as one where the writer is faced with death and discovers the beauty of life or some such thing. But Cody, raised on aesthetics, says “I do love being alive, sitting here with this first edition of the Cantos my father gave me—and maybe, you may well argue, the house is too thick and the paintings a shade too oiled (and the old voice lifts itself, weaving an endless sentence), and you may well be right—but my goodness, fuck you, I happen to be so happy here with all these gifts and words and all these selves.” And if you yourself have been in this position of having a doctor refer to your imminent death and the chemotherapy you need to receive and if you have browsed the bookstore’s self-help-dying-cancer shelves and thought “pure dreck,” then Joshua Cody is right there with you:

If there are some people who require disease to teach them such things then fine, but I am not, was not one of those those, thank you very much. I loved life and found beauty and sources of pleasure in things on the outside and on the inside, and illness was not an opportunity for existential awakenings, it was the very opposite of beauty or grace, it was a harrowing, a descensus: and then it went down.

More than Wallace, this attitude (and the opening scene of receiving a chemotherapy treatment) call to mind, to me at least, Walter White and Breaking Bad. The nearness of death accentuates the urgency of life while also accentuating its inherent suffering, its opposition to neat and tidy endings. Both Cody and Walter White show us that the relatively commonplace occurrence of cancer can lead not only to introspection and carpe diem, but also to sad risk-taking and (personal and public) failures.

Wallace says “What the really great artists do is they’re entirely themselves. They’re entirely themselves, they’ve got their own vision, they have their own way of fracturing reality, and if it’s authentic and true, you will feel it in your nerve endings.†Joshua Cody is a great artist, entirely himself, and in [sic], while we watch him flay his own nerve endings and try to mend them back together again, we see glimpses of our selves.