InfiniteWinter: AA books davidfosterwallace dfw InfiniteJest

by mattbucher

2 comments

To Risk Sentimentality

“Sentimental” is one of the worst charges a critic can level at a book. Sometimes the insult is couched in “overly sentimental” or other adjectives and adverbs intended to soften the blow, but any novel that deals extensively with overt sadness or tenderness will likely have to weather such a criticism or work hard to preemptively avoid it. The challenge is for those novels to rebut the label of sentimentality by proving that they are in fact not exaggerating the magnitude of suffering or slipping off into the embarrassing territory of self-indulgent storytelling, but rather to risk seeming sentimental in order to emotionally connect with readers. I would argue that Infinite Jest succeeds in hoeing very close to the boundaries of sentimentality without stepping over them. Though Wallace stated in interviews that Infinite Jest was about “sadness” of some form or the other, that sadness is not existential, but is a symptom of some other, deeper problem.

The Big Book of AA doesn’t give a shit about sentimentality. It starts out with the surprisingly unsentimental and straightforward tale of the group’s founder, Bill W. His story is written in the first person and the story’s goals are not primarily literary, though it is laced through with supremely sophisticated rhetoric. Bill W. writes simple, declarative lines like: “I was very lonely and again turned to alcohol,” which intentionally don’t tug at heartstrings or exaggerate or euphemize what is the foundation of all AA rock-bottom stories. If you’ve read Infinite Jest and heard enough of these AA rock-bottom stories, then Bill W.’s story is what you might expect: here was a successful Wall Street banker and alcohol ruined his life. He compresses much of the story down and even skips over the worst of his binges with candid phrases like “drinking caught up with me again” or “I went on a prodigious bender.”

Bill W.’s story is so sad because of the prolonged period wherein he knows he must, absolutely must stop drinking and yet is unable to find the resolve to quit drinking on his own. This genuinely perplexes him. He desperately wants to quit drinking, but every hospital he tries only keeps him dry for a few weeks. When he gets home, every time, he says “the courage to do battle was not there.” Simple self-knowledge or awareness is not what saves him from an early grave. What saves him, in the end, is a chance meeting with an old friend—a former alcoholic who has found religion.

Bill W.’s story lacks the syrupy sentimentality we might expect because ultimately, like Infinite Jest, it is a story about personal enlightenment. Hal’s own path towards enlightenment involves wrestling his way out of the cage of loneliness: We enter a spiritual puberty where we snap to the fact that the great transcendent horror is loneliness, excluded encagement in the self. Once we’ve hit this age, we will now give or take anything, wear any mask, to fit, be part-of, not be Alone, we young. It is this very encagement that shoots down the very thought of sentimentality or engaging deeply with one’s own emotions in order to make peace with them. We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony at a young age where the face is fictile enough to assume the shape of whatever it wears. And then it’s stuck there, the weary cynicism that saves us from gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naiveté. Sentiment equals naiveté on this continent (at least since the Reconfiguration).

Part of what Wallace is arguing here is that there is no such thing as authentically transcending sentimentality. To do so only denies one’s self access to true humanity. “Hal, who’s empty but not dumb, theorizes privately that what passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human, at least as he conceptualizes it is probably to be unavoidably sentimental and naive and goo-prone and generally pathetic, is to be in some basic interior way forever infantile, some sort of not-quite-right-looking infant dragging itself anaclitically around the map, with big wet eyes and froggy-soft skin, huge skull, gooey drool. One of the really American things about Hal, probably, is the way he despises what it is he’s really lonely for: this hideous internal self, incontinent of sentiment and need, that pulses and writhes just under the hip empty mask, anhedonia.” Another name for that hip, cool mask is irony. (The worst thing about irony for me is that it attenuates emotion.)

When Bill W. meets his formerly alcoholic friend and asks him how he has obtained this new-found sobriety, the friend says point blank “I’ve got religion.” This is one solution that Bill W. had not seriously considered. Something innate in him resisted the idea of giving up control of his life to a higher power. But yet he is interested in any program that would lead to lasting sobriety. This paradox is the climax of Bill’s story, which feels somewhat postmodern (especially for a story published in 1939) because the complex solution to saving his life turns out to be relatively simple. The whole point of AA is the attempt to find this power greater than (and thus outside of) one’s self. Bill looks at his now-sober friend and admits “It began to look as though religious people were right after all. Here was something at work in a human heart which had done the impossible. My ideas about miracles were drastically revised right then.” What allows Bill W. to change his mind about “God” and religion and higher powers is the tacit permission to choose his own conception of God. When the grace is unshackled from dogma, it transforms him for good.

The challenge of AA is to get new members to accept this basic fact: they must give up control of their lives to a Higher Power. The challenge of writing fiction about human emotions is to get readers to identify and empathize with characters instead of just pitying them.

In a 2013 interview, George Saunders talked about some conversations he’d had with David Foster Wallace and other writers about this very subject.

[Saunders] described making trips to New York in the early days and having “three or four really intense afternoons and evenings with”, on separate occasions, Wallace and Franzen and Ben Marcus, talking to each of them about what the ultimate aspiration for fiction was. Saunders added: “The thing on the table was emotional fiction. How do we make it? How do we get there? Is there something yet to be discovered? These were about the possibly contrasting desire to: (1) write stories that had some sort of moral heft and/or were not just technical exercises or cerebral games; while (2) not being cheesy or sentimental or reactionary.” {emphasis added}

To empathize, one must truly see outside of one’s self. It is a process of forgetting the self. The “destruction of self-centeredness” is the price to be paid for sobriety, AA will tell you. Part of that involves a traditionally religious idea of servitude, sacrificing for others over and over, “in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.” The alternative is not just the default setting we are stuck with (or literal godlessness–the ultimate solitude), it is the modern and postmodern rat race, “the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.”

There is a myopic idea in the academic world of Wallace Studies that DFW & empathy has been “done.” Time to move along, now. Because they seem to lack sophistication and were covered early on, the recurring ideas of irony, sentimentality, and loneliness (or whatever) no longer hold appeal for the scholars who are, by the very nature of current scholarship, required to find some worthy topic that has been thus-far neglected. No one has written a dissertation on bird imagery in Wallace’s work so it’s suddenly “neglected” (for example) or maybe we do need more on Wallace’s work as it relates to race and gender and sexuality or analytic philosophy and political theory or any number of topics. But “empathy” was not just another topic Wallace was throwing out there for scholars to explore. This nexus of empathy-sentimentality-and “moral heft” gets to the DNA of who Wallace was as a writer and what he was hoping to accomplish in his art. Academics and critics can easily stand back and observe what it must take for a fictional character (which is basically what Wallace Himself is now anyway) to destroy “self-centeredness” but it is a uniquely human experience (rather than a purely cerebral one) for the realer, more enduring and sentimental part of one’s actual self to take charge and command that other part of the self to keep silent, “as if looking it levelly in the eye and saying, almost aloud, ‘Not another word.'”

Readers Anonymous: DFW’s Transformative Gifts and the Labor of Gratitude

What is it that compels thousands of strangers to organize themselves, both on the internet and in person, for the sole purpose of talking to each other about David Foster Wallace’s writing? With the exception of maybe Pynchon, I can’t think of another figure in contemporary American literature whose readers generate and engage in so much collaborative work.

By way of personal example, here’s a list of the Wallace projects I frequently consult for help with my writing or to clarify my thinking about DFW:

- Nick Maniatis’s thehowlingfantods.com

- The Wallace-l listerv

- Infinite Winter (website, subreddit, Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, Google+ if that’s your thing)

- Infinite Summer (same as above, plus its own 1,100-member forum)

- The Great Concavity Podcast

- Two Illinois State University Conferences (and a third this year)

- The Paris & London Conferences plus an upcoming Australian one

- Chris Ayers’ Poor Yorick Entertainment tumblr, “A Visual Exploration of the Filmography of James O. Incandenza“

- Text-specific wikis and utilities pages

The few times I’ve been lucky enough to make some small contribution to projects like these, I’ve always come away from the experience feeling like I’m running on rocket fuel. Collaborative work has the unique ability to remind me why it was that I started writing about Wallace in the first place. Whatever my level of participation, I always get back far more than what I put in.

But none of the items on this list would exist without the dedicated folks who maintain them and whose involvement far exceeds anything that could reasonably be called “participation.” Given the amount of labor required, what drives those who devote their time and energy to the creation and maintenance of projects like these? My palms start to sweat just thinking about the 17+ years of aggregate effort required to keep the lights on over at thehowlingfantods.com, to say nothing of the anxiety inherent in hosting an international conference (writing and distributing a CFP, reading and jurying submissions, sending out approval- and rejection notices, negotiating hotel group-rates, enduring headaches from the university’s legal department, catering meals, printing programs, talking down maniac academics in mid-freakout because their presentations’ AV-setups don’t work, and who-knows-what-else).

The only plausible theory for this kind of dedication to an author’s work I’ve come across (other than sheer psychosis) is Lewis Hyde’s conception of “gift economies,” which he outlines in his book The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World. Before I get into that, I should probably say here that the connection between Hyde & Wallace is interesting to me for a couple of reasons:

1) In the obligatory “Praise for” section of The Gift’s opening pages is a blurb from Wallace:

The Gift actually deserves the hyperbolic praise that in most blurbs is so empty. It is the sort of book that you remember where you were and even what you were wearing when you first picked it up. The sort that you hector friends about until they read it too. This is not just formulaic blurbspeak; it is the truth. No one who is invested in any kind of art, in questions of what real art does and doesn’t have to do with money, spirituality, ego, love, ugliness, sales, politics, morality, marketing, and whatever you call “value,” can readThe Gift and remain unchanged.

2) DFW’s copy of The Gift, now housed at UT Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, has Wallace’s annotations in it.

Hyde, who worked for several years as a counselor to alcoholics in the detoxification ward of a city hospital, presents the recovery program of Alcoholics Anonymous as a prime example of a “transformative gift,” one which must be offered without thought of return. In a footnote on page 74 (2006 ed.) Hyde reasons that for alcoholics, AA’s “gift” is a function of a the program’s (previously–mentioned) spiritual requirement, ”the belief in a higher power”:

Alcoholics who get sober in AA tend to become very attached to the group, at least to begin with. Their involvement seems, in part, a consequence of the fact that AA’s program is a gift. In the case of alcoholism, the attachment may be a necessary part of the healing process. Alcoholism is an affliction whose relief seems to require that the sufferer be bound up in something larger than the ego-of-one (in a “higher power,” be it only the power of the group). Hearings that call for differentiation, on the other hand, may be more aptly delivered through the market.(93 fn)

It’s a sort of hermeneutics of recovery: the only membership-requirement of Alcoholics Anonymous is “a desire to stop drinking,” which desire almost nobody truly has without hitting bottom. Time and again, AA’s official literature seems to go out of its way to remind newcomers that it’s only in the depths of such a low that most alcoholics are willing to submit to the rigors of the program. This receptiveness in the early days of AA’s program of recovery is doubly important because the next step after an honest and sincere desire to quit drinking is often the most difficult: the surrendering of will to a higher power. And here again, this may explain the pains taken by AA’s literature when it emphasizes over and over that this higher power can take whatever form a member chooses. In Infinite Jest, Wallace talks about this kind of hardcore receptiveness as the only real prerequisite for recovery:

The bitch of the thing is that you have to want to. If you don’t want to do as you’re told ”I mean as it’s suggested you do” it means that your own personal will is still in control[.] The will you call your own ceased to be yours as of who knows how many Substance-drenched years ago. […] This is why most people will Come In and Hang In only after their own entangled will has just about killed them. […] You have to want to take the suggestions, want to abide by the traditions of anonymity, humility, surrender to the Group conscience. If you don’t obey, nobody will kick you out. They won’t have to. You’ll end up kicking yourself out, if you steer by your own sick will. (357)

And in what seems to me a ridiculously convenient coincidence (in terms of the present argument), Hyde actually chooses AA as his analogue for explaining the circular nature of transformational gifts:

[M]ost artists are converted to art by art itself. The future artist finds himself or herself moved by a work of art, and, through that experience, comes to labor in the service of art until he can profess his own gifts. Those of us who do not become artists nonetheless attend to art in a similar spirit. We come to painting, to poetry, to the stage, hoping to revive the soul. And any artist whose work touches us earns our gratitude. […] for it is when art acts as an agent of transformation that we may correctly speak of it as a gift. A lively culture will have transformative gifts as a general feature“ it will have groups like AA which address specific problems, it will have methods of passing knowledge from old to young, it will have spiritual teachings available at all levels of maturation and for the birth of the spiritual self. (48)

To restate this passage for our purposes here: The best art is transformative for author and reader alike. Whether one is the giver or receiver of transformational art is merely a function of one’s position in the cycle. The transformational gift is passed freely from giver to recipient, who, transformed by gratitude, feels a duty to pass the gift on to the next recipient. This last step is the same gratitude-inspired service that AA’s 5th tradition and 12th step refer to: the transformational gift of AA, received by those able to “hang in there and keep coming back,” is that (as yet another AA maxim goes) “it works if you work it.” And this is where recovery’s hermeneutic process cycles back into itself: working the 12th step is the point at which the recipient, no longer a newcomer “having been transformed by AA’s gift” can assume the role of the giver by sponsoring new members. Here’s Wallace’s take on this cyclical process:

Giving It Away is a cardinal Boston AA principle. The term’s derived from an epigrammatic description of recovery in Boston AA: “You give it up to get it back to give it away.” Sobriety in Boston is regarded as less a gift than a sort of cosmic loan. You can’t pay the loan back, but you can pay it forward, by spreading the message that despite all appearances AA works, spreading this message to the next new guy who’s tottered in to a meeting and is sitting in the back row unable to hold his cup of coffee. (344)

Comparing that last quotation to Hyde’s description of the reciprocal relationship between gifts and gratitude, several parallels become apparent:

In each example I have offered of a transformative gift, if the teaching begins to “take,” the recipient feels gratitude. I would like to speak of gratitude as a labor undertaken by the soul to effect the transformation after a gift has been received. Between the time a gift comes to us and the time we pass it along, we suffer gratitude. Moreover, with gifts that are agents of change, it is only when we have come up to its level, as it were, that we can give it away again. Passing the gift along is the act of gratitude that finished the labor. The transformation is not accomplished until we have the power to give the gift on our own terms. Therefore, the end of the labor of gratitude is similarity with the gift or with its donor. Once this similarity has been achieved we may feel a lingering and generalized gratitude, but we won’t feel it with the urgency of true indebtedness. (48)

I can’t think of a better illustration of this labor of gratitude, gratitude for a gift of such immensity and meaning that it inspires the recipient’s own selfless giving than what you can find written on the flyleaves of the UF library’s copy of The Big Book:

One last thing: Hyde describes the gift-recipient’s “transformation” as one that produces a similarity with the gift or with its donor. As I re-read the AA sections of Infinite Jest, I can’t help but understand Wallace’s use of the word “identification” to mean anything other than this process of achieving similarity.In these sections of the novel, Wallace manages to show us precisely the part of recovery that Boston AA’s newcomers can’t see ”even though the gift’s transformation is already underway.”

To Toil and Not to Seek for Rest: Prayer in Infinite Jest

There are no atheists in halfway houses. Of course, they might enter the door as self-identified agnostics or nonbelievers, but to maintain a residence as part of a 12-step recovery program at such a halfway house they will be required to at least go through the motions. Rob mentioned that many, many of the earliest AA members butted up against this “higher power” requirement and declared that they were agnostics, too. AA, of course, butted right back and said Just Do It, Fake it Til You Make It, etc. And if you can’t fathom a higher power, AA itself can be your higher power. But here’s another barrier you might have: pray to this higher power. And this requirement might cause one to step back and contemplate just what is prayer, really?

“and when people with AA time strongly advise you to keep coming you nod robotically and keep coming, and you sweep floors and scrub out ashtrays and fill stained steel urns with hideous coffee, and you keep getting ritually down on your big knees every morning and night asking for help from a sky that still seems a burnished shield against all who would ask aid of it ” how can you pray to a ‘God’ you believe only morons believe in, still?”

At the end of his 1996 interview with David Foster Wallace, David Lipsky looks around Wallace’s house and sees a postcard tacked to the wall. That postcard contains the prayer of St. Ignatius.

Lord, teach me to be generous

To serve you as you deserve

To give and not to count the cost

To fight and not to heed the wounds

To toil and not to seek for rest

To labor and not ask for reward,

Save that of knowing that I do your will.

This is often called “St. Ignatius’s Prayer or the Prayer for Generosity. (BTW, Richard Powers wrote a book shortly after Wallace’s death called Generosity that includes a writing instructor who is losing is faith in writing. And Ignatius immediately calls to mind Ignatius J. Reilly, to me. There are a lot of parallels between Confederacy of Dunces and Infinite Jest, and of course John Kennedy Toole was a depressive who committed suicide at a young age.)

In Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, Lipsky says this reminds him of the AA prayer, which is also known as the Serenity Prayer. The Serenity Prayer is probably repeated at 99% of all AA meetings. However, there are some other AA/12-step prayers related to specific needs or steps.

http://www.12steps.org/12stephelp/prayers.htm

The full version of the Serenity Prayer, written by Reinhold Niebuhr goes like this:

God, give me grace to accept with serenity

the things that cannot be changed,

Courage to change the things

which should be changed,

and the Wisdom to distinguish

the one from the other.

Living one day at a time,

Enjoying one moment at a time,

Accepting hardship as a pathway to peace,

Taking, as Jesus did,

This sinful world as it is,

Not as I would have it,

Trusting that You will make all things right,

If I surrender to Your will,

So that I may be reasonably happy in this life,

And supremely happy with You forever in the next.

This longer version (which is not the one oft-repeated at AA) adds several AA concepts like accepting hardship, One Day at a Time, and surrendering the will as a requirement for reasonable happiness.

But in the halfway house, reasonable happiness is often far in the distance. An Ennet House resident drops in to Pat Montesian’s office and says “I’m awfully sorry to bother. I can come back. I was wondering if maybe there was any special Program prayer for when you want to hang yourself.”

Gately struggles, though not as fatalistically, with the prayer thing.

“He says when he tries to pray he gets this like image in his mind’s eye of the brainwaves or whatever of his prayers going out and out, with nothing to stop them, going, going, radiating out into like space and outliving him and still going and never hitting Anything out there, much less Something with an ear. Much much less Something with an ear that could possibly give a rat’s ass. He’s both pissed off and ashamed to be talking about this instead of how just completely good it is to just be getting through the day without ingesting a Substance, but there it is.”

Wallace works hard to convey exactly how AA works, and these moments of clarity or epiphany are the end results of that mysterious process, what is essentially a new form of belief. In a fantastic essay published in The Legacy of David Foster Wallace, Lee Konstantinou writes that “What Wallace wants is not so much a religious correction to secular skepticism allegedly run amok as new forms of belief—the adoption of a kind of religious vocabulary (God, prayer, etc.) emptied out of specific content, a vocabulary engineered to confront the possibly insuperable condition of postmodernity.” There is another post coming on that idea of “a vocabulary engineered to confront” but what rings true here is the way AA functioned (both in fiction and reality) as a new system of belief and a blueprint for life for Wallace.

Zadie Smith told us that “This was his literary preoccupation: the moment when the ego disappears and you’re able to offer up your love as a gift without expectation of reward. At this moment the gift hangs, like Federer’s brilliant serve, between the one who sends and the one who receives, and reveals itself as belonging to neither. We have almost no words for this experience of giving. The one we do have is hopelessly degraded through misuse. The word is prayer.”

Big Books and “Meaning as Use”

You see by this what I meant when I called pragmatism a mediator and reconciler and said that she “unstiffens” our theories. She has in fact no prejudices whatsoever, no obstructive dogmas, no rigid canons of what shall count as proof. She is completely genial. She will entertain any hypothesis, she will consider any evidence.

In short, she widens the field of search for God.

William James, Pragmatism

Since my last post, I’ve read (at least) two things that merit further consideration in this conversation about A.A. and Infinite Jest.

One has to do with Tom Bissell’s recent piece in the Times, which is apparently an excerpt from his introduction to the forthcoming 20th-anniversary edition of Wallace’s own Big Book. This part in particular elicited a reaction from one of my eyebrows:

“While I have never been able to get a handle on Wallace’s notion of spirituality, I think it is a mistake to view him as anything other than a religious writer. His religion, like many, was a religion of language.

I agree with Bissell that to understand Wallace (at least post-Jest Wallace) as anything other than a religious writer is a mistake—but only with the caveat that “religious” here means something very specific and non-doctrinaire. However, I’m confused by Tom Bissell’s confession of difficulty re: getting a handle on Wallace’s spirituality. Maybe this is some sort of rhetorical strategy on Bissell’s part; perhaps the introduction to an 1,100-page novel isn’t the place to launch into a paean to Alcoholics Anonymous. Alright, fine: it’s definitely not.

But if he truly means what he says that he “can’t get a handle on” Wallace’s notion of spirituality he must not have looked very hard. Wallace mentions spirituality and religion all over the place, from interviews with Brian Garner and Larry McCaffery, to the Kenyon speech, to nonfiction essays like “The Nature of the Fun,” to Infinite Jest itself. What’s more, Wallace is pretty consistent about what he says. And I’d argue this consistency stems from Wallace’s fidelity to (what I understand as) the source of his first serious engagements with religion: his participation in A.A.

But in typical Wallace fashion, he couldn’t just take what A.A. said about spirituality on faith; he had to do his own research. At least one of the texts Wallace consulted for this research was Huston Smith’s The World’s Religions: Our Great Wisdom Traditions (which by the time Wallace read it had been re-issued and re-titled; it was originally published as The Religions of Man).

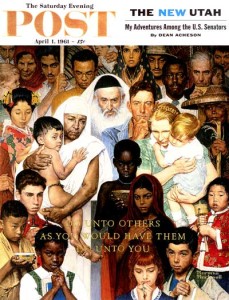

Here’s a picture of the cover of the 1991 ed. like the one owned and annotated by Wallace, which copy is available for viewing at UT’s Harry Ransom Center:

The cover image is a reproduction of a Norman Rockwell’s “Golden Rule,” a piece that first appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1961. (A mosaic version of the piece still hangs in the United Nations building in New York.) The text that sits on top of the image, Do unto others as you would have them do unto you is there in the original, as in Rockwell put it there.

I mention this here because I think it goes a long way toward helping us “get a handle on Wallace’s notion of spirituality.”

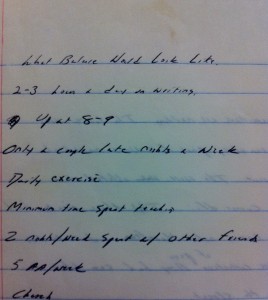

By way of evidence, here’s a photo of some of Wallace’s annotations in the Smith text, via (as ever!) Matt:

Here’s a transcription with Wallace’s underlining for clarity’s sake:

Might not becoming a part of a larger, more significant whole relieve life of its triviality? That question announces the birth of religion. For though in some watered-down sense there may be a religion of self-worship, true religion begins with the quest for meaning and value beyond self-centeredness. It renounces the ego’s claims to finality.

But what is this renunciation for? The question brings us to the two signposts on the Path of Renunciation. The first of these reads “the community,” as the obvious candidate for something greater than ourselves. In supporting at once our own life and the lives others, the community has an importance no single life can command. Let us, then, transfer our allegiance to it, giving its claims priority over our own.

This transfer marks the first great step in religion. It produces the religion of duty, after pleasure and success the third great aim of life in the Hindu outlook. Its power over the mature is tremendous. Myriads have transformed the will-to-get into the will-to-give, the will-to-win into the will-to-serve. Not to triumph but to do their best to acquit themselves responsibly, whatever the task at hand has become their prime objective.

And in the margin next to this underlining is Wallace’s note: AA.

I do not mean here to equate the underscoring of a passage with its unequivocal or uncritical endorsement. But neither do I think it a stretch to say that Wallace had read the A.A. literature closely enough to see in this passage from Smith the core principles of spirituality as they’re presented by Alcoholics Anonymous: the twin necessities of self-renunciation via the relinquishment of the will to a power greater than oneself, and the consequent undertaking of work in service of others. As The Big Book (cribbing KJV’s James 2) cautions: faith without works is dead.

The second thing that warrants mentioning: Anyone who’s read The Broom of the System knows how ham-fistedly Wittgenstein’s “meaning as use” maxim gets deployed in Wallace’s first novel. And I think one of the things that allowed Wallace to suspend his disbelief about the A.A.-mandated belief in a power greater than himself was the way the Big Book conceptualizes the notions of “meaning” and “use” as intrinsically bound up with one another. In the A.A. model, Wittgenstein’s aphorism is applied not just to language, but to the rather more immediate case of the recovering alcoholic struggling to cope with life after alcohol. In this context, asking “What’s the meaning of life?” is to ask “What is the use of my life?” or “Am I useful to others?”

This notion of “usefulness” and its relation to the “default-mode” of self-centeredness Wallace talks about in the commencement is one that crops up again and again in A.A.’s Big Book:

Never was I to pray for myself, except as my requests bore on my usefulness to others. Then only might I expect to receive. […]Simple, but not easy; a price had to be paid. It meant the destruction of self-centeredness (13-14).

In fact, the concept of service work, “passing it on,” as it is codified in one A.A. maxims is directly and repeatedly correlated with the chances of a successful recovery:

For if an alcoholic failed to perfect and enlarge his spiritual life through work and self-sacrifice for others, he could not survive the certain trials and low spots ahead. If he did not work, he would surely drink again, and if he drank he would surely die. Then faith would be dead indeed. With us it is just like that. […] Faith has to work twenty-four hours a day in and through us, or we perish (14-16); Our very lives, as ex-problem drinkers, depend upon our constant thought of others and how we may help meet their needs (20); Whatever our protestations, are not most of us concerned with ourselves, our resentments, or our self-pity? Selfishness, self-centeredness! That, we think, is the door of our troubles. [¦] So our troubles, we think, are basically of our own making. They arise out of ourselves, and the alcoholic is an extreme example of self-will run riot, though he usually doesn’t think so. Above everything, we alcoholics must be rid of this selfishness. We must, or it kills us! (BB 62).

Ultimately, the mere cessation of drinking is presented as not finally the point; it is rather a means to another rehabilitation; it is a restoration of the capacity for service:

At the moment we are trying to put our lives in order. But this is not an end in itself. Our real purpose is to fit ourselves to be of maximum service to God and the people about us (77).

The more connections I see between A.A. and David Foster Wallace, the more inclined I am to read the process of writing Infinite Jest as a function of “working the steps.” And if Wallace was sincere about working them, which I believe he was, this sincerity has a certain bearing on questions that get asked over and over about the novel.

In that often-cited interview I mentioned earlier, Wallace and McCaffery get to talking about form and contemporary American fiction. Wallace has, a couple of paragraphs back, just finished praising William Vollmann’s remarkable integrity because Vollmann doesn’t engage in formal extravagance or experimentation for its own sake. McCaffery follows up by asking about Wallace’s own experiments with form, to which Wallace gives his standard-issue response about the way Infinite Jest is structured–that certain formal choices in the novel (e.g. the endnotes) were made in order to solicit an amount of readerly work, and that this work is supposed to highlight the fact that IJ’s narrative is by its very nature a mediated thing. In other words, the formal features are there to encourage readers to understand themselves as participating in a conversation with the writer. McCaffery counters with a rather pointed question:

“LM: How is this insistence on mediation different from the kind of meta-strategies you yourself have attacked as preventing authors from being anything other than narcissistic or overly abstract or intellectual?

DFW: I guess I’d judge what I do by the same criterion I apply to the self-conscious elements you find in Vollmann’s fiction: do they serve a purpose beyond themselves?

I think that by Infinite Jest, Wallace has developed a writing ethic that is something like a pragmatic amalgam of Wittgenstein and A.A.’s notion of meaning-as-use. And I think it shows up in the writing, especially when comparing Wallace’s two novels. By Infinite Jest, the toll of Wallace’s personal experiences of addiction and recovery have changed what he lets himself get away with in his writing, theory- and form-wise.

And with regard to those changes, a final A.A. maxim seems apposite here, one that must have had a particularly dark inflection for Wallace: My best thinking got me here.

Infinite Jest as Moral Novel

What is the point of life?

In this 1996 interview with Chris Lydon, Wallace says that somehow the present culture has taught us that “really the point of living is to get as much as you can and experience as much pleasure as you can and the implicit promise is that will make you happy.” That’s a sort of simplistic overview of the whole novel’s theme, but it fits with the ideas related to why alcohol and other pleasurable substances maybe don’t ultimately lead to happiness. So, if pleasure and entertainment are not at the core life’s purpose, what is? Or what should be?

The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous starts out by trying to convince you that you are an alcoholic. Pretty much every defense you can think of to rationalize getting drunk is refuted, or at least diffused, right up front. The idea of the responsible “gentleman drinker” whom every alcoholic aspires to be is debunked as myth right out of the gate. AA teaches you that the solution to stopping drinking is what we sometimes call “soul-searching” or what the Big Book sometimes calls being “properly armed with facts” about one’s self. This soul-searching leads to abandoning pride, a “confession of shortcomings” and the inevitable conclusion that the ability to stop drinking lies outside of one’s self.

Chapter 2 of the Big Book states the result of this soul-searching pretty starkly:

The great fact is just this, and nothing less: That we have had deep and effective spiritual experiences which have revolutionized our whole attitude toward life, toward our fellows and toward God’s universe. The central fact of our lives today is the absolute certainty that our Creator has entered into our hearts and lives in a way which is indeed miraculous. He has commenced to accomplish those things for us which we could never do by ourselves.

This is the organization that Ennet House requires its residents to attend every week. When life becomes impossible, they send you to AA.

In the book we are presented with many case studies of substance abuse, but the two most prominent are Don Gately and Hal Incandenza. One is forced into a halfway house after years of drugs and crime. The other is just starting to experience the spiritual side-effects of substances. We think of Hal as primarily a pot smoker, but he also drinks.

Hal’s mother, Mrs. Avril Incandenza, and her adoptive brother Dr. Charles Tavis, the current E.T.A. Headmaster, both know Hal drinks alcohol sometimes, like on weekend nights with Troeltsch or maybe Axford down the hill at clubs on Commonwealth Ave.; The Unexamined Life has its notorious Blind Bouncer night every Friday where they card you on the Honor System. Mrs. Avril Incandenza isn’t crazy about the idea of Hal drinking, mostly because of the way his father had drunk, when alive, and reportedly his father’s own father before him, in AZ and CA; but Hal’s academic precocity, and especially his late competitive success on the junior circuit, make it clear that he’s able to handle whatever modest amounts she’s pretty sure he consumes — there’s no way someone can seriously abuse a substance and perform at top scholarly and athletic levels, the E.T.A. psych-counselor Dr. Rusk assures her, especially the high-level-athletic part — and Avril feels it’s important that a concerned but un-smothering single parent know when to let go somewhat and let the two high-functioning of her three sons make their own possible mistakes and learn from their own valid experience, no matter how much the secret worry about mistakes tears her gizzard out, the mother’s.

Right here we are introduced to a family with a history of alcohol abuse (which ended in suicide for Hal’s father), a protective and worried mother, a private-school system that is so ingrained in equating success with the ability to “handle” substances that it tolerates a degree of underage drinking in the process. Wallace is quite clever in entertaining the reader (a blind bouncer!) as he doles out these diagnoses of systematic, societal-level problems that it lulls the reader into believing we are now insiders aware of all this modern-conundrum stuff too, but in the end don’t we want things to turn out well? Can’t we all just get along?

And Charles supports whatever personal decisions she [Avril] makes in conscience about her children. And God knows she’d rather have Hal having a few glasses of beer every so often than absorbing God alone knows what sort of esoteric designer compounds with reptilian Michael Pemulis and trail-of-slime-leaving James Struck, both of whom give Avril a howling case of the maternal fantods. And ultimately, she’s told Drs. Rusk and Tavis, she’d rather have Hal abide in the security of the knowledge that his mother trusts him, that she’s trusting and supportive and doesn’t judge or gizzard-tear or wring her fine hands over his having for instance a glass of Canadian ale with friends every now and again, and so works tremendously hard to hide her maternal dread of his possibly ever drinking like James himself or James’s father, all so that Hal might enjoy the security of feeling that he can be up-front with her about issues like drinking and not feel he has to hide anything from her under any circumstances.

What Avril values is this need for security and honesty when in fact her choices have created the exact opposite of her intentions. Hal is not open and honest with her about anything. He smokes pot in secret, addicted more to the solitude and self-punishment than the substance itself. He does not feel secure in the world or in his emotionally distant relationships.

The answers to the questions about how should one live are not answered explicitly in Infinite Jest, they are implied and inferred. The first step involves seeking meaning outside of one’s self, outside of the cage of one’s head. And at a very basic level, that’s the definition of religion.

David Foster Wallace, Alcoholics Anonymous, and “Everybody Worships”

I should probably explain how this all started.

A couple months ago, I was listening to the November 5th episode of Matt & Dave Laird’s “The Great Concavity” podcast when, around the 22-minute mark, the conversation turned to Wallace’s Kenyon College commencement address. At this point in the podcast, they’re discussing the section where Wallace talks specifically about which things it’s OK for us to worship and therefore derive our sense of meaning from. Drawing a distinction, Matt noted:

He [Wallace] says something about “If you worship money and things,” if that’s where you get, you know, your meaning out of life, you’ll never have enough. If you worship this other thing, if you worship beauty and sexual allure, you’ll always feel ugly, you’ll die a million deaths. All that stuff is him saying: “Don’t worship anything except a higher being.” And that’s really where I think me and Wallace personally, like as a philosophy, part ways in that I disagree with that. And I think that that’s not the definition of “atheism” because he says: “in the day-to-day trenches of adult life there’s no such thing as atheism,” and he says: “everyone worships.” And I say worshiping is different than a belief in a higher power. […] You can tap real meaning in life from something that is not centered out of a higher power. And he says: no, it has to be, and for me that’s a little bit different.

Matt’s distinction is interesting to me in a couple of ways. First, this part of the commencement speech had stuck in my craw for what sounds like the same reasons Matt cites. Though my grandfather was a Methodist minister and I grew up going to church, I don’t consider myself to be a religious person–at least not in the dogmatic or doctrinal senses that “religious” generally connotes. Second, I line up with Wallace’s opinion just about always, and so for Wallace to restrict the acceptable places for me to “tap real meaning” to a list of outmoded spiritual traditions had bothered me. Just so we’re on the same page, this is the relevant sentence from Wallace’s address:

The compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of God or spiritual-type thing to worship, be it J.C. or Allah, be it Yahweh, or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles, is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

I wondered, “What’s the commonality between the items on this list that keep them from eating us alive?” Do these traditions share some particular quality that keeps them from ultimately bending back inward, toward the self, that keeps them from cultivating in us the selfish desire to accumulate and display the things that Wallace names: money, beauty, power, intellectual mastery? Why this particular list?

The answer has everything to do with Wallace’s phrasing. His wording here provides a clue, I think, to his source material.

As Matt mentioned in his last post, I’m finishing up a dissertation on Wallace. Specifically, I’m using a Recovery Studies framework to cast the differences between Wallace’s use of theory in his first and second novels as those of a “recovering theory-addict.” And back when I listened to this episode of TGC, I’d been working on a chapter that looked at the influence of 12-step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous on Infinite Jest. Consequently, the language of AA’s central text (technically titled Alcoholics Anonymous but usually referred to in meetings as The Big Book to avoid confusion with the program itself) was still fresh in my mind. And so as I listened again to the commencement address, Wallace’s phrasing, “God or spiritual-type thing”and the plurality of choices in his list of religious traditions had a familiar ring to it.

The particular resonance I heard (and continue to hear) occurs in chapter 4 of The Big Book, titled “We Agnostics.” In the chapters that lead up to it, alcoholism is presented as a self-inflicted problem, with the self here understood as a tripartite construction comprised of the “mind, body, and crucially, the spirit of the alcoholic. This “spiritual” side of the self is basically the human capacity for numinous or spiritual experience—something like the feeling of being moved emotionally by the sublime. The Big Book presents it as an explanation for the preponderance of religions in so many disparate cultures, for the “persistence of the myth” whether it be true or not. But most importantly, they see this innate spiritual capacity as something that is exceptionally and singularly human. In the “We Agnostics” chapter, The Big Book elaborates on how this third component, the alcoholic’s spiritual or metaphysical aspect, must be reformed.

In it, we read that as agnostics, some of the first members of AA had difficulty following the second step. This amounts to a fairly big problem for someone in AA because the rest of the 12 steps hang on the acceptance of the first two: “1. We admitted we were powerless over alcohol, that our lives had become unmanageable and 2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” Now, writing as former agnostics who had been able to overcome their skepticism, the authors are at pains to tell why we think our present faith is reasonable, why we think it more sane and logical to believe than not to believe, why we say our former thinking was soft and mushy when we threw up our hands in doubt and said “We don’t know.” I’ll spare you the quotation of the entire argument, but it basically boils down to this: when the agnostics looked closely at what held them back from being “restored to sanity” through belief in a “Power greater than [them]selves,” they found it was another belief, a belief in their own ability to reason, or a faith in their reasonable faculties:

…let us think a little more closely. Without knowing it, had we not been brought to where we stood by a certain kind of faith? For did we not believe in our own reasoning? Did we not have confidence in our ability to think? What was that but a sort of faith? Yes, we had been faithful, abjectly faithful to the God of Reason. So, in one way or another, we discovered that faith had been involved all the time!

Now, with regard to the “particular resonance” I mentioned hearing above, this next bit is where the bells started going off:

We found, too, that we had been worshippers. […] Had we not variously worshipped people, sentiment, things, money, and ourselves? […] Who of us had not loved something or somebody? How much did these feelings, these loves, these worships, have to do with pure reason? Little or nothing, we saw at last. Were not these things the tissue out of which our lives were constructed? Did not these feelings, after all, determine the course of our existence? It was impossible to say we had no capacity for faith, or love, or worship. In one form or another we had been living by faith and little else.

The authors go on to explain that the matter of their conversion was no small thing; if they had not been primed to accept the necessity of handing over their wills to a higher power, they probably wouldn’t have been able to do it, save that they had recently experienced a particular event in the narrative common to all addicts: hitting bottom. And at the point in David Foster Wallace’s life when The Big Book crosses his path, hitting bottom is precisely where he found himself.

I think that ultimately, the items on Wallace’s approved worship-list are there because they’re traditions that direct us toward a love of something outside of ourselves as their primary principles Christianity’s first two commandments, for example, are to “Love God with the entirety of the heart, intellect, and will,” and that basically, if the first commandment is properly understood and followed, that you can’t help but follow the second: love others as yourself. The spiritual traditions that make up Wallace’s list are variations on that same theme (something like Augustine’s “Love, then do what thou wilt”).

The realization that Wallace drew on this passage (and many others) from The Big Book for his writing continues to affect my own thinking and writing in numerous ways. At the very least, it shapes the way I read Wallace’s usual obsessions—everything from sincerity and authenticity to formal concerns like the role of metafictional technique.

The Big Book and Infinite Jest

In an interview, Cormac McCarthy famously said “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” Infinite Jest is no exception. The books that Wallace drew on for inspiration while constructing his novel include Don DeLillo’s End Zone, The Cinema Book, and many others. Perhaps the book least familiar to me but most familiar to Wallace and the most influential on Infinite Jest is the core text of Alcoholics Anonymous, titled simply The Big Book.

In conjunction with the 2016 Infinite Winter project, Rob Short and I will post here on various ways The Big Book, other AA literature, and AA in general helped shape Wallace’s fictional project. This issue also intersects with other major themes and topics at work in the novel, including the ideas of belief, faith, morality, and agnosticism so we will likely get into those issues, too.

This blog will not be “spoiler-free.” That’s probably not ideal for first-time readers of the novel. However, the book has been out for 20 years now and there is a sizable population of readers who have read the book or re-read the book several times.

I’ll let Rob write a formal introduction (if he chooses!) but you should know that he is a PhD candidate at the University of Florida, writing about David Foster Wallace. The work he has presented at the DFW conferences in Illinois is remarkable because it consistently breaks new scholarly ground, but is highly accessible (and relevant) to general readers. He and I have discussed these issues (about Wallace and AA and “worship”) privately for a while now, but I figured this is as good a time as any to invite others into the conversation and help us work out these ideas more publicly.