books: 1990s books disobedience drinkard fiction novels

by mattbucher

leave a comment

Disobedience by Michael Drinkard

This book was recommended to me by a friend on Instagram and the description looked good so I picked it up, and once I started reading it I was immediately hooked.

The book was published in 1993 and it’s so right-in-my-wheelhouse that I am still sorta shocked I had not heard of it or come across it before 2022. It’s a madcap comedy, it’s a multi-generational saga, it’s a Gen X snapshot, it’s a history of orange groves in Southern California, and much more. At various points it reminded me of Girl with Curious Hair, Less than Zero, Mark Leyner, Pynchon, DeLillo, and many others. Also, for a book that came out in 1993, it’s remarkably prescient in its depiction of near-future technologies.

Drinkard is perhaps best known as the spouse of writer Jill Eisenstadt, whose novel From Rockaway is a stone-cold classic of 20th Century American fiction. But Drinkard should be better known and now I’m off to read his other two novels.

For anyone just picking up Disobedience, I’ve created a little cheat sheet to the cast of characters below. [Warning: I’m not posting any of the true spoilers here but there are some spoiler-ish details below, but I don’t think any of it will impact your enjoyment of the book.]

Characters

Luther Tibbets, Eliza Tibbets – earliest timeline, they plant the original orange trees and struggle to have children

Franklin Wells – “contemporary” storyline – he is the father of Aaron and Billybones

Mavy Tibbets – mother of Aaron and Billybones, granddaughter of Eliza and Luther Tibbets

Bernie Tibbets – father of Mavy, author of Ripcord

Aaron Wells – parents are Franklin and Mavy, 14 years old in the latest “near-future” timeline

Billybones Wells – youngest child of Franklin and Mavy

Linda Delgado – subject of Aaron’s desire

Jimbo – classmate of Aaron

Brainy – classmate of Aaron

Prudey – classmate of Aaron

Serena & Manny Delgado – Linda’s parents

Caroline – Franklin’s girlfriend after Mavy, only 5 years older than Aaron

John – tomato farmer interested in Mavy

Grandma Goretex – Mrs. Wells – Franklin’s mother, former Vegas showgirl

President McKinley – he actually was in California in 1901

Granny Fanny – born 1901, Mavy’s grandma

Victoria – Franklin’s boss at Solvtex

Stoddard Manville – Franklin’s rival at Solvtex (Franklin mockingly calls him ArManiville as a play on “Armani”-ville)

Annie – Mavy’s therapist

InfiniteWinter: AA books davidfosterwallace dfw InfiniteJest

by mattbucher

2 comments

To Risk Sentimentality

“Sentimental” is one of the worst charges a critic can level at a book. Sometimes the insult is couched in “overly sentimental” or other adjectives and adverbs intended to soften the blow, but any novel that deals extensively with overt sadness or tenderness will likely have to weather such a criticism or work hard to preemptively avoid it. The challenge is for those novels to rebut the label of sentimentality by proving that they are in fact not exaggerating the magnitude of suffering or slipping off into the embarrassing territory of self-indulgent storytelling, but rather to risk seeming sentimental in order to emotionally connect with readers. I would argue that Infinite Jest succeeds in hoeing very close to the boundaries of sentimentality without stepping over them. Though Wallace stated in interviews that Infinite Jest was about “sadness” of some form or the other, that sadness is not existential, but is a symptom of some other, deeper problem.

The Big Book of AA doesn’t give a shit about sentimentality. It starts out with the surprisingly unsentimental and straightforward tale of the group’s founder, Bill W. His story is written in the first person and the story’s goals are not primarily literary, though it is laced through with supremely sophisticated rhetoric. Bill W. writes simple, declarative lines like: “I was very lonely and again turned to alcohol,” which intentionally don’t tug at heartstrings or exaggerate or euphemize what is the foundation of all AA rock-bottom stories. If you’ve read Infinite Jest and heard enough of these AA rock-bottom stories, then Bill W.’s story is what you might expect: here was a successful Wall Street banker and alcohol ruined his life. He compresses much of the story down and even skips over the worst of his binges with candid phrases like “drinking caught up with me again” or “I went on a prodigious bender.”

Bill W.’s story is so sad because of the prolonged period wherein he knows he must, absolutely must stop drinking and yet is unable to find the resolve to quit drinking on his own. This genuinely perplexes him. He desperately wants to quit drinking, but every hospital he tries only keeps him dry for a few weeks. When he gets home, every time, he says “the courage to do battle was not there.” Simple self-knowledge or awareness is not what saves him from an early grave. What saves him, in the end, is a chance meeting with an old friend—a former alcoholic who has found religion.

Bill W.’s story lacks the syrupy sentimentality we might expect because ultimately, like Infinite Jest, it is a story about personal enlightenment. Hal’s own path towards enlightenment involves wrestling his way out of the cage of loneliness: We enter a spiritual puberty where we snap to the fact that the great transcendent horror is loneliness, excluded encagement in the self. Once we’ve hit this age, we will now give or take anything, wear any mask, to fit, be part-of, not be Alone, we young. It is this very encagement that shoots down the very thought of sentimentality or engaging deeply with one’s own emotions in order to make peace with them. We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony at a young age where the face is fictile enough to assume the shape of whatever it wears. And then it’s stuck there, the weary cynicism that saves us from gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naiveté. Sentiment equals naiveté on this continent (at least since the Reconfiguration).

Part of what Wallace is arguing here is that there is no such thing as authentically transcending sentimentality. To do so only denies one’s self access to true humanity. “Hal, who’s empty but not dumb, theorizes privately that what passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human, at least as he conceptualizes it is probably to be unavoidably sentimental and naive and goo-prone and generally pathetic, is to be in some basic interior way forever infantile, some sort of not-quite-right-looking infant dragging itself anaclitically around the map, with big wet eyes and froggy-soft skin, huge skull, gooey drool. One of the really American things about Hal, probably, is the way he despises what it is he’s really lonely for: this hideous internal self, incontinent of sentiment and need, that pulses and writhes just under the hip empty mask, anhedonia.” Another name for that hip, cool mask is irony. (The worst thing about irony for me is that it attenuates emotion.)

When Bill W. meets his formerly alcoholic friend and asks him how he has obtained this new-found sobriety, the friend says point blank “I’ve got religion.” This is one solution that Bill W. had not seriously considered. Something innate in him resisted the idea of giving up control of his life to a higher power. But yet he is interested in any program that would lead to lasting sobriety. This paradox is the climax of Bill’s story, which feels somewhat postmodern (especially for a story published in 1939) because the complex solution to saving his life turns out to be relatively simple. The whole point of AA is the attempt to find this power greater than (and thus outside of) one’s self. Bill looks at his now-sober friend and admits “It began to look as though religious people were right after all. Here was something at work in a human heart which had done the impossible. My ideas about miracles were drastically revised right then.” What allows Bill W. to change his mind about “God” and religion and higher powers is the tacit permission to choose his own conception of God. When the grace is unshackled from dogma, it transforms him for good.

The challenge of AA is to get new members to accept this basic fact: they must give up control of their lives to a Higher Power. The challenge of writing fiction about human emotions is to get readers to identify and empathize with characters instead of just pitying them.

In a 2013 interview, George Saunders talked about some conversations he’d had with David Foster Wallace and other writers about this very subject.

[Saunders] described making trips to New York in the early days and having “three or four really intense afternoons and evenings with”, on separate occasions, Wallace and Franzen and Ben Marcus, talking to each of them about what the ultimate aspiration for fiction was. Saunders added: “The thing on the table was emotional fiction. How do we make it? How do we get there? Is there something yet to be discovered? These were about the possibly contrasting desire to: (1) write stories that had some sort of moral heft and/or were not just technical exercises or cerebral games; while (2) not being cheesy or sentimental or reactionary.” {emphasis added}

To empathize, one must truly see outside of one’s self. It is a process of forgetting the self. The “destruction of self-centeredness” is the price to be paid for sobriety, AA will tell you. Part of that involves a traditionally religious idea of servitude, sacrificing for others over and over, “in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.” The alternative is not just the default setting we are stuck with (or literal godlessness–the ultimate solitude), it is the modern and postmodern rat race, “the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.”

There is a myopic idea in the academic world of Wallace Studies that DFW & empathy has been “done.” Time to move along, now. Because they seem to lack sophistication and were covered early on, the recurring ideas of irony, sentimentality, and loneliness (or whatever) no longer hold appeal for the scholars who are, by the very nature of current scholarship, required to find some worthy topic that has been thus-far neglected. No one has written a dissertation on bird imagery in Wallace’s work so it’s suddenly “neglected” (for example) or maybe we do need more on Wallace’s work as it relates to race and gender and sexuality or analytic philosophy and political theory or any number of topics. But “empathy” was not just another topic Wallace was throwing out there for scholars to explore. This nexus of empathy-sentimentality-and “moral heft” gets to the DNA of who Wallace was as a writer and what he was hoping to accomplish in his art. Academics and critics can easily stand back and observe what it must take for a fictional character (which is basically what Wallace Himself is now anyway) to destroy “self-centeredness” but it is a uniquely human experience (rather than a purely cerebral one) for the realer, more enduring and sentimental part of one’s actual self to take charge and command that other part of the self to keep silent, “as if looking it levelly in the eye and saying, almost aloud, ‘Not another word.'”

Best Books I Read in 2013

Not all of these books were published in 2013, but most were. I haven’t been great about tracking all the books I’ve read, but these were the most memorable.

1. S. by Doug Dorst (with J.J. Abrams)

I’m a sucker for books about books, and books about fictional reclusive authors, and I’m also a sucker for books with printed ephemera inserted throughout, and books with marginalia all over them and books about the sea. So, this book pushed a lot of buttons for me. If you haven’t read Dorst’s previous books, I highly recommend those as well. “Ship of Theseus”, the Straka novel at the center of S., is a masterpiece in its own right. I look forward to re-reading this book. (And even though Abrams’ name is on the cover of the book, make no mistake, this is a Doug Dorst book.)

2. Traveling Sprinkler by Nicholson Baker

Not even going to apologize for my love of all things Nick Baker. I credit him with getting me seriously interested in literature. This one continues the story of Paul Chowder and Baker feels so human to me here because he embraces a contemporary world that looks a lot like my own (i.e. the ubiquity and necessity of iPhones, going to the gym, listening to pop music, etc.).

3. Anti Lebanon by Carl Shuker

If you aren’t familiar with Carl Shuker’s writing, you need to go out and buy The Method Actors. If you are familiar with Shuker, you probably greet a new book from him the way some people treat the release of a new Jay Z album (or equivalent). When this book came out in early 2013, it was a big deal to me. It’s a geographical (and thematic) departure for Shuker, which is exciting, but his mastery of dialogue and sense of a character’s internal philosophy shines throughout. Check out biblioklept’s review of the book as well.

4. The High Life by Jean-Pierre Martinet

This short novella is about a misanthropic narrator in Paris. Â I was drawn to it because it is so short and looked experimental, and I’d never heard of Martinet. The Introduction in the book explains a lot about his life and career as a writer, which was mostly a failure. None of this sounds like a ringing endorsement, but to me, the book had a purity to it that made Martinet’s alter ego somewhat endearing. It felt like reading a black and white French film.

5. May We Be Forgiven by A.M. Homes

This novel was a return-to-form for Homes. It reminded me a lot of Music for Torching, but felt more developed or mature beyond that. I’ll read anything by Homes, but I like her best when she inhabits characters like these and tells a straightforward story.

6. The Afterlife by Donald Antrim

When Antrim was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship this year, I was inspired to go back and read the one book of his I hadn’t yet picked up—his memoir. It’s a dark story about his mother and alcoholism, but there are a lot of layers to the story and I found humor there, too (especially in his quest to find the perfect bed). It’s a brave book.

I picked this up at Comic-con in San Diego and it was the best reading material I had all summer. It’s a dense book full of stories, panels, interviews, and behind-the-scenes stuff that it gave me an entirely new perspective on Clowes.

8. Happy Talk by Richard Melo

One of the gifts of literature is that you get to experience thoughts, ideas, and places in a voice you would not imagine on your own. Richard Melo’s novel Happy Talk continually surprised me because common clichés were absent or interrupted and clear care was taken with each line of dialogue and prose. The end result is not just surprise but delight. Happy Talk is the story of a group of American nurses stationed in Haiti during World War II. But it’s also one of those novels where telling someone what it’s “about†conveys very little of what the experience of reading it is like. Melo is, in part, a painter of images. A few lasting ones: the picture of the nurse rippling a bedsheet over her head and watching it descend slowly, the parachutist dangling from a tree, and the Nation of Islam building a UFO.

9. Mumbai New York Scranton by Tamara Shopsin

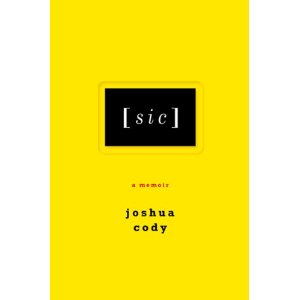

This is a memoir by the daughter of famous NY restaurateur Kenny Shopsin. Right away, this sold me on the book because I love Shopsins restaurant (the old location in the Village) and the documentary about Shopsins (I Like Killing Flies). However, Tamara Shopsin proves herself to be a talented writer and artist in her own right. It reminded me of a couple of my favorite recent memoirs: Patti Smith’s Just Kids and Joshua Cody’s [sic].

books: books bothfleshandnot davidfosterwallace dfw federer review

by mattbucher

2 comments

D.F. Wallace Both Flesh and Not

Like many others, I greet the publication of this collection of nonfiction pieces, Both Flesh and Not, by David Foster Wallace, with a little bit of trepidation. For one, I’ve read all this stuff already. Granted, I am a devoted fan of DFW’s, but I’d reckon that almost every fan of his has read either the Federer essay or his Salon.com list of under-appreciated novels or one of the other shorter pieces in this collection for free, online. So that’s a little disappointing. There’s nothing here previously unpublished or expanded or gleaned from his recently opened archives at the Harry Ransom Center. But I am glad this book exists and that it pours into concrete book-form some of Wallace’s lesser-known essays.

The title piece, “Federer Both Flesh and Not” (from which the book sorta takes its title) was published in the New York Times “Play” magazine under the title “Federer as Religious Experience.” The version here is exactly the same as that published in the New York Times. Wallace’s editor at “Play,” Josh Dean, writes about “how much [Wallace] cared about every single letter in an 11,000-word story” and then later quotes a letter from Wallace saying “I’ve got the fucker down to like 8,400 words. Another maybe 100-200 words can come out without much problem, if need be. Cutting much more from that will cripple the piece, which I’ve worked hard on and feel protective of. (If you decided, for instance, that you want to run only like 5,000 words of it, I wouldn’t do it — I’d settle for the Kill Fee.†And then we learn: “Another 100 or so words were trimmed for space, and the piece ran as Play’s cover story on August 20, 2006.” My question is: why not give us the 11,000 word version here in the book? Maybe we’d get to see more of the “religious” storyline or more rococo detail about Federer’s beautiful moves (“Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip”). Why not restore it all when you are not bound by the strict printed-word limits of the New York Times? I don’t get it.

Roger Federer has been directly asked about this piece several times and he’s said he admires the piece. Here he is 2009 when asked about it:

Q. There were times during your match today when I was reminded of an essay by the late American author, David Foster Wallace. It’s called “Roger Federer as Religious Experience.” I’m wondering if you have heard of this essay, read it, or what you think of it?

ROGER FEDERER: Sure, I remember his piece. I remember doing the interview here on the grounds, up on the grass. I had a funny feeling walking out of the interview. I wasn’t sure what was going to come out of it, because I didn’t know exactly what direction he was going to go. The piece was obviously fantastic. You know, yeah, it’s completely different to what I’ve read in the past about me anyway.

But one of his joking comments caused a minor stir. The Italian paper La Stampa published an interview with Federer in September 2009:

Foster Wallace wrote that seeing Federer play was like a religious experience.

I did an interview with him at Wimbledon for half an hour, one of the strangest I’ve ever done. As I was leaving I was still wondering what we had talked about. I was very [stricken]* by his suicide.

Have you any idea about that?

I hope, I’m sure it was not because of me. … Artists like him have high level ideals, which often do not hold up, unfortunately, the confrontation with life. He wrote a wonderful essay about me. Thanks to him, also, the world is a better place for me.

That “stricken” [molto colpito] could also be interpreted as “impressed” or “affected”, (it’s not clear what language the interview was conducted in before it was translated into Italian) but the hint that Wallace’s suicide “was not because of me” seems odd here because in the context of the interview, it feels like it’s Federer’s way of pointing up what an absurd question it is for him to comment on, and yet Federer still manages to append a couple of genuinely heartfelt and eloquent sentences after that moment. Still, some fools tried to connect Federer’s decline (or Sarah Palin’s nomination) with Wallace’s suicide and Sports Illustrated’s tennis writer was asked about the comments to the point that he had to clarify “Just to put this rest, I’m sure Federer was right: He did not trigger Wallace’s suicide.” That said, at the 2012 New Yorker Festival in October, Mark Costello made the point that, before his death, Wallace just “couldn’t write anymore” and that the Federer piece “was the last time that his ass left the chair”, meaning that Wallace was so inspired while writing it that he no longer felt his ass in the chair. So maybe it’s not entirely fair to say that there is no connection at all between this essay on Federer and Wallace’s own decline.

Unless you read the flap copy, there is no indication from the front or back cover that this book contains the seminal essay about Roger Federer—and one of the best extant essays about contemporary tennis, period. (There is a standalone Italian edition. DFW is very big in Italy. And there is an illustrated version.) I don’t know how many other reviewers will be compelled to draw comparisons between Federer and Wallace—the best essayist writing about the best tennis player. Of course the title of “best” is subjective and only grudgingly granted, and always fleeting. Wallace is gone, Nadal and Djokovic have surpassed Federer (though, at this very moment, Federer is back atop the ATP rankings {or near the top, it changes frequently}). Wallace claims that seeing Federer play live at Wimbledon is a “near-religious experience.” Even then, he has to qualify it with near.”

Of course, this insight is nothing new. Sublime victory on the playing field has been compared to religious ecstasy thousands of time before (just ask Yankees fans). However, the narrative of Federer winning Wimbledon was not thrilling or ecstatic so much as routine (in 2006, at least) so what Wallace is talking about in terms of “religious experience” is something else, something related to the beauty of an athlete who is able to routinely use his body to do the seemingly impossible. This resembles the beauty of Wallace’s writing to me: something bound not by a thrilling narrative or personality, but the depth of action between the baselines of the page.

“Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young” is an important essay about a group of fiction writers who all emerged around the same time in the early 1980s. He wrote this essay in the Fall of 1987 after he’d submitted his MFA thesis and taken a short-term gig teaching at his alma mater, Amherst.

“Back in New Fire” is a piece that DFW probably never collected because the argument, even couched in “ifs” and “but so then”, could sound completely hideous: AIDS is a blessing?? The piece first appeared in Dave Eggers’ Might magazine under the title “Impediments to Passion” and was collected in the Might anthology, Shiny Adidas Track Suits and the Death of Camp, under the title “Hail the Returning Dragon, Clothed in New Fire.” Not sure where the title “Back in New Fire” comes from, but it isn’t Wallace’s.

http://www.theknowe.net/dfwfiles/pdfs/Wallace-Hail_the_Returning_Dragon.pdf

I have this very slight notion that Wallace got the idea for this piece while he was in the halfway house in Boston. One bit in support of that idea is this remembrance by a fellow AA member in Bloomington, IL:

Dave shared a story once with ”there was a newcomer in a meeting no, I think somebody had come back from a relapse. And he shared this story about when he was in the halfway house. And he said they always had like these people that’d come in and they would kind of educate you about some life skills. And this person talked about the AIDS virus and how it lives in very dark places, dark, damp places. And that it’s not airborne. And he made the relationship for the newcomer about alcoholism. And that once you talk about it, it loses its power over you. Once you talk about what’s going on, it loses its power. And that person just lit up with this confidence that they could, you know, stay sober, they could do this. He was very generous with sharing his experience with people, his struggles, and I don’t know.

Jay Jennings, the former editor of Tennis Magazine, who in 1996 commissioned Wallace to write an article about the U.S. Open (“Democracy and Commerce at the U.S. Open”), donated the page proofs of that essay to the Ransom Center’s collection.

Wallace’s reviews of Borges: A Life and The Best American Prose Poem are excellent, but I really wish that this collection had included even more pieces (see Ryan Niman’s excellent bibliography at The Knowe for the most complete list of Wallace’s unpublished or uncollected nonfiction). I mean, if you are going to go all out and collect the stuff then why leave out Wallace’s early book reviews (of Clive Barker’s Great and Secret Show, J.G. Ballard’s War Fever, Dead Elvis by Greil Marcus, and others). Also missing is Wallace’s introduction, titled Quo Vadis, to the issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction that he guest edited. That piece includes gems like this:

I have observed in myself a kind of sine-wavelike cycle of interest and boredom and interest in riding herd on a project like this. In a way, it’s sort of like my cycle of feelings about religion. To me, religion is incredibly fascinating as a general abstract object of thought—it might be the most interesting thing there is. But when it gets to the point of trying to communicate specific or persuasive stuff about religion, I find I always get frustrated or bored.

Or it would be nice to see the long contributor’s note he drafted for the Best American Short Stories 1992. These omissions just open the door for another (albeit slim) volume to be published later.

The lists of words that run between essays are nice, but don’t add much in this context. I’d rather see just a reprint of the list of words without the definitions or maybe a nice reproduction of one of the handwritten pages housed in the Ransom Center. One neat addendum to this book is this ad, which ran in the same issue of Rain Taxi as Wallace’s review of The Best American Prose Poem, and includes his blurb for Davis’s book (“Probably well worth checking out”) and the small-type disclaimer: “Paid for by the reviewer of The Best American Prose Poem: An International Journal.”

If you are a collector of all-things-DFW, you probably ordered this book and have already reread it (since you likely read the contents of it long ago). You will remove it from its box, turn it over, glance at it, and kindly shelve it in the Ws. If you love tennis and/or beautiful sentences, you need to stop and read “Federer Both Flesh and Not.”

The Art of Fielding

UPDATE: I wrote this little review like a year ago and didn’t publish it because I was not thrilled with Harbach’s book. The reasons for not liking the book were fairly elusive, though, because I did read the whole thing and didn’t fling it out the window or anything. I was trying to find something positive to say about the novel, and well, the positives just didn’t add up to much. I would be interested in other perspectives.

Chad Harbach’s novel The Art of Fielding appears this month [Oct 2011] from Little, Brown. In the Kindle Single documenting the path-to-publication of the novel, Keith Gessen reminds us that Harbach’s publisher and editor are also the publisher and editor of David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest (Little, Brown and Michael Pietsch). Although the blurb on the front (and back!) cover make it clear that this is more Franzen territory than another DFW imitator, there are a couple of similarities: the tennis academy/baseball college and the gravedigging.

The most obvious influence on The Art of Fielding, however is Moby-Dick. There are a lot of times where Harbach does all but say “it’s like in Moby-Dick how…” or “Starbuck…sorry, I mean Starblind,” but I don’t mean to chalk this up as a negative. There is a big reading audience out there for novels about college, baseball, and Moby-Dick, and I fit in there, too.

The novel does a good job of showing us the inner lives of these college boys without veering off into a celebration of “bro” culture. [There is even a special term for two bros on the same baseball team who do everything together a la Schwartzy and Skrimshander: basebromance.] Harbach sets himself up with some stereotypes that he must somehow surpass–and for the most part he does.

Harbach paints a convincing portrait of Skrimshander and Schwartzy (and even Affenlight), but Pella remains an enigma—the damsel in distress, discovering herself again, falling for the wrong guy, a walking cliché; it gets harder and harder to visualize her as a real person in this otherwise-convincing reality drama.

paleking: books davidfosterwallace dfw Italy paleking palewinter

by mattbucher

1 comment

Pale Winter

The great DFW Italian site Archivio DFW is hosting a group read of The Pale King called “Pale Winter” (aka #palewinter). I contributed a short essay (here: “Always Another Word“) that was translated into Italian by Roberto Natalini. Below is the English version of that post. Many thanks to Roberto and Andrea Firrincieli.

———————————————————————————————-

Like any posthumous novel, The Pale King comes to us from the hands of an editor. All novels are edited, but those assembled by editors after an author’s death face the dual burdens of shaping a narrative and a legacy. At their core, novels are sequences of words laid out end-to-end. The sequencing matters. Infinite Jest would be a different novel altogether if the first seventeen pages were moved to the end of the book—or if the end notes became footnotes. We have no way of knowing how David Foster Wallace wanted the various sections of The Pale King assembled. The version we have now was painstakingly assembled by his longtime editor, Michael Pietsch. Pietsch’s care and attention to detail are apparent—as are the challenges of his job.

It is extremely difficult to stay alert and attentive instead of getting hypnotized by the constant monologue inside your own head. . . .”Learning how to think” really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. . . . .The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline.

We see him now as a brave writer who struggled against the force that wanted him to shed himself. Years from now, we’ll still feel the chill that attended news of his death. One of his recent stories ends in the finality of this half sentence: Not another word.But there is always another word. There is always another reader to regenerate these words. The words won’t stop coming. Youth and loss. This is Dave’s voice, American.

I take comfort in that. There is always another word and another reader. And today that reader is you.

[sic] by Joshua Cody

Joshua Cody’s new memoir [sic] is partly the story of how he—a young man living in New York City, a composer, a descendant of Buffalo Bill Cody—was diagnosed with cancer (a lymphoma of some sort, he never really says) and the treatment didn’t work and he had to get a bone marrow transplant, but really it’s mostly the story of what it’s like to be inside Joshua Cody’s head. One thing fiction (and memoir) teaches us, one of its greatest assets is that it’s possible (and good) to think beyond our selves—to actively try to adopt another’s point of view. David Foster Wallace says it way better than me: “I guess a big part of serious fiction’s purpose is to give the reader, who like all of us is sort of marooned in her own skull, to give her imaginative access to other selves.†And then in the same breath Wallace goes on to explain some of the same stuff about suffering that Joshua Cody is dealing with in [sic]:

Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience, more like a sort of “generalization†of suffering. Does this make sense? We all suffer alone in the real world; true empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside. It might just be that simple.

But we’re getting a little ahead of our selves here. Both Wallace and Cody struggle with knowing something long and complex and looking at it, think “How do I tell this story? Where do you begin? How about this little bit here? Is that really the beginning? Bear with me while I go back and explain…†This struggle to deal with narrative and the flow of the story/plot reflects a lifelong struggle to live in a way that is not constantly fracturing and forking off in different directions. But that does not mean the story and the life are formless. Cody is a trained composer, a musician. He is deeply concerned about form and framing.

Cody is clearly a David Foster Wallace fan—and Wallace’s struggle with depression and eventual suicide haunt him. “Our greatest writer. As if I wasn’t thinking of him during that whole thing. My God. As if he hadn’t helped.” Cody contemplates killing himself (in a scene reminiscent of The Royal Tenenbaums), standing in front of a mirror, well actually “it was me between two mirrors, producing an infinite line of selves, like at the end of Citizen Kane.” And the crucial question he finds before him is: “How do we position suffering in human life?” And this is where it gets interesting, because maybe we think of a cancer memoir as one where the writer is faced with death and discovers the beauty of life or some such thing. But Cody, raised on aesthetics, says “I do love being alive, sitting here with this first edition of the Cantos my father gave me—and maybe, you may well argue, the house is too thick and the paintings a shade too oiled (and the old voice lifts itself, weaving an endless sentence), and you may well be right—but my goodness, fuck you, I happen to be so happy here with all these gifts and words and all these selves.” And if you yourself have been in this position of having a doctor refer to your imminent death and the chemotherapy you need to receive and if you have browsed the bookstore’s self-help-dying-cancer shelves and thought “pure dreck,” then Joshua Cody is right there with you:

If there are some people who require disease to teach them such things then fine, but I am not, was not one of those those, thank you very much. I loved life and found beauty and sources of pleasure in things on the outside and on the inside, and illness was not an opportunity for existential awakenings, it was the very opposite of beauty or grace, it was a harrowing, a descensus: and then it went down.

More than Wallace, this attitude (and the opening scene of receiving a chemotherapy treatment) call to mind, to me at least, Walter White and Breaking Bad. The nearness of death accentuates the urgency of life while also accentuating its inherent suffering, its opposition to neat and tidy endings. Both Cody and Walter White show us that the relatively commonplace occurrence of cancer can lead not only to introspection and carpe diem, but also to sad risk-taking and (personal and public) failures.

Wallace says “What the really great artists do is they’re entirely themselves. They’re entirely themselves, they’ve got their own vision, they have their own way of fracturing reality, and if it’s authentic and true, you will feel it in your nerve endings.†Joshua Cody is a great artist, entirely himself, and in [sic], while we watch him flay his own nerve endings and try to mend them back together again, we see glimpses of our selves.