books: 1990s books disobedience drinkard fiction novels

by mattbucher

leave a comment

Disobedience by Michael Drinkard

This book was recommended to me by a friend on Instagram and the description looked good so I picked it up, and once I started reading it I was immediately hooked.

The book was published in 1993 and it’s so right-in-my-wheelhouse that I am still sorta shocked I had not heard of it or come across it before 2022. It’s a madcap comedy, it’s a multi-generational saga, it’s a Gen X snapshot, it’s a history of orange groves in Southern California, and much more. At various points it reminded me of Girl with Curious Hair, Less than Zero, Mark Leyner, Pynchon, DeLillo, and many others. Also, for a book that came out in 1993, it’s remarkably prescient in its depiction of near-future technologies.

Drinkard is perhaps best known as the spouse of writer Jill Eisenstadt, whose novel From Rockaway is a stone-cold classic of 20th Century American fiction. But Drinkard should be better known and now I’m off to read his other two novels.

For anyone just picking up Disobedience, I’ve created a little cheat sheet to the cast of characters below. [Warning: I’m not posting any of the true spoilers here but there are some spoiler-ish details below, but I don’t think any of it will impact your enjoyment of the book.]

Characters

Luther Tibbets, Eliza Tibbets – earliest timeline, they plant the original orange trees and struggle to have children

Franklin Wells – “contemporary” storyline – he is the father of Aaron and Billybones

Mavy Tibbets – mother of Aaron and Billybones, granddaughter of Eliza and Luther Tibbets

Bernie Tibbets – father of Mavy, author of Ripcord

Aaron Wells – parents are Franklin and Mavy, 14 years old in the latest “near-future” timeline

Billybones Wells – youngest child of Franklin and Mavy

Linda Delgado – subject of Aaron’s desire

Jimbo – classmate of Aaron

Brainy – classmate of Aaron

Prudey – classmate of Aaron

Serena & Manny Delgado – Linda’s parents

Caroline – Franklin’s girlfriend after Mavy, only 5 years older than Aaron

John – tomato farmer interested in Mavy

Grandma Goretex – Mrs. Wells – Franklin’s mother, former Vegas showgirl

President McKinley – he actually was in California in 1901

Granny Fanny – born 1901, Mavy’s grandma

Victoria – Franklin’s boss at Solvtex

Stoddard Manville – Franklin’s rival at Solvtex (Franklin mockingly calls him ArManiville as a play on “Armani”-ville)

Annie – Mavy’s therapist

streetview: Google Street View GoogleMaps GSV photos streetview

by mattbucher

leave a comment

Some Recent GSV Images

I haven’t posted here in forever so this is really just a test, but I still post images I find on Google Street View over on my Tumblr: buchr.tumblr.com

Here are a few recent faves

Things I have seen on Google Street View

My window to the world is a Dell P2411H digital display. Google, via its many Street View cars, has photographed millions of miles of roadways and made those panoramic images easily available online. I look at Google Street View, or GSV, every day. I take screenshots of things that interest me and post them on a Tumblr page. Over the past seven years I have posted nearly three thousand screenshots. Some of the things I see are fascinating but do not translate well visually, even in a cropped screenshot. Sometimes I wonder about the people I see photographed by the Street View cameras. Sometimes I think about them long after I have forgotten where on the map they exist. I have favorite places that I return to, over and over.

Hong Kong

A boy, no more than 10 years old, walking by himself, his face glued to his Nintendo DS.

Dallas

A restaurant called C’VICHE, whose manager I imagine ordering supplies from Sysco or some other giant purveyor of basic foodstuffs elsewhere in Dallas Fort Worth Metroplex and having to specify, insistently over the phone, “See, apostrophe, vee, eye, see, aitch, eee. Suh-vee-chay. No first e, though. No, I mean, there is an e, but it’s at the end. No, not two e’s though…Where the first e should be is an apostrophe. . . Like suh-vichy . . . . Fuck it. Kuh-vitch. Just call us kuh-vitch. Cavitch here.â€

Bangladesh

Looking at crowds of people on the streets of Dhaka, I wonder does anyone in the United States know the names of any of these people? Can any non-Bangladeshi name another Bangladeshi at all? All those Chandnis and Meghs and Shamims and Sumons and their lives are totally invisible to me. What is their sense of their own place in the world’s history? What do they aspire to do in their lives? This image of them through the eyes of the Google Street View lens is my only view of them at all. And again I look at crowds on the streets of Lima and wonder at the masses of unknown lives and names that will never gain prominence outside of their own town, their own neighborhood or street perhaps. Hector Rodriguez? Jaime Saltillo? Maria Jimenez? Who are they? And this has always been the history of the world. Masses of unknowns. How much I will never know. Would I even want to know? Have I made a conscious choice to not know?

Botswana

The trees are low and the sun is relentless. Near the border of Zimbabwe is a border post with a sign stating “Let us keep our border clean‖as if Zimbabwe insists on officially littering and Botswana is reduced to begging: “please, let us just keep this area clean.†But I’m sure it’s just a nuance of their colonial English that means “help us†keep the border clean. Unless it’s some sort of racial cleansing statement. The border area itself looks as clean and well-kept as any in the US-Mexico border areas I’ve seen. There are some tin shacks just West of the border crossing that look like they serve as a de facto market and food court.

Arvin, California

A picnic in a park. Ten hispanic men in cowboy hats crowded around a single picnic table. An elderly white man on a mountain bike cautiously approaches them from the sidewalk.

Lower Hutt, Wellington, New Zealand

A store called Krazzy 4 Bollywood. I assume the second z is because they are truly crazy, I mean, CRAZY for Bollywood. Not even replacing the C with a K can explain how crazy they are about Bollywood movies. But then I Google it learn there is a Bollywood comedy called “Krazzy 4†and thus the store’s name operates as a clever pun as well as a signal to those in the know.

Rural France

A family walking hand-in-hand, each parent holding a child’s hand and a picnic basket, bypassing a restaurant, headed toward a pasture.

InfiniteWinter: AA books davidfosterwallace dfw InfiniteJest

by mattbucher

2 comments

To Risk Sentimentality

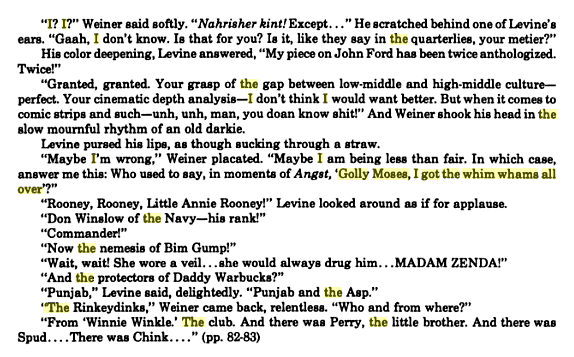

“Sentimental” is one of the worst charges a critic can level at a book. Sometimes the insult is couched in “overly sentimental” or other adjectives and adverbs intended to soften the blow, but any novel that deals extensively with overt sadness or tenderness will likely have to weather such a criticism or work hard to preemptively avoid it. The challenge is for those novels to rebut the label of sentimentality by proving that they are in fact not exaggerating the magnitude of suffering or slipping off into the embarrassing territory of self-indulgent storytelling, but rather to risk seeming sentimental in order to emotionally connect with readers. I would argue that Infinite Jest succeeds in hoeing very close to the boundaries of sentimentality without stepping over them. Though Wallace stated in interviews that Infinite Jest was about “sadness” of some form or the other, that sadness is not existential, but is a symptom of some other, deeper problem.

The Big Book of AA doesn’t give a shit about sentimentality. It starts out with the surprisingly unsentimental and straightforward tale of the group’s founder, Bill W. His story is written in the first person and the story’s goals are not primarily literary, though it is laced through with supremely sophisticated rhetoric. Bill W. writes simple, declarative lines like: “I was very lonely and again turned to alcohol,” which intentionally don’t tug at heartstrings or exaggerate or euphemize what is the foundation of all AA rock-bottom stories. If you’ve read Infinite Jest and heard enough of these AA rock-bottom stories, then Bill W.’s story is what you might expect: here was a successful Wall Street banker and alcohol ruined his life. He compresses much of the story down and even skips over the worst of his binges with candid phrases like “drinking caught up with me again” or “I went on a prodigious bender.”

Bill W.’s story is so sad because of the prolonged period wherein he knows he must, absolutely must stop drinking and yet is unable to find the resolve to quit drinking on his own. This genuinely perplexes him. He desperately wants to quit drinking, but every hospital he tries only keeps him dry for a few weeks. When he gets home, every time, he says “the courage to do battle was not there.” Simple self-knowledge or awareness is not what saves him from an early grave. What saves him, in the end, is a chance meeting with an old friend—a former alcoholic who has found religion.

Bill W.’s story lacks the syrupy sentimentality we might expect because ultimately, like Infinite Jest, it is a story about personal enlightenment. Hal’s own path towards enlightenment involves wrestling his way out of the cage of loneliness: We enter a spiritual puberty where we snap to the fact that the great transcendent horror is loneliness, excluded encagement in the self. Once we’ve hit this age, we will now give or take anything, wear any mask, to fit, be part-of, not be Alone, we young. It is this very encagement that shoots down the very thought of sentimentality or engaging deeply with one’s own emotions in order to make peace with them. We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony at a young age where the face is fictile enough to assume the shape of whatever it wears. And then it’s stuck there, the weary cynicism that saves us from gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naiveté. Sentiment equals naiveté on this continent (at least since the Reconfiguration).

Part of what Wallace is arguing here is that there is no such thing as authentically transcending sentimentality. To do so only denies one’s self access to true humanity. “Hal, who’s empty but not dumb, theorizes privately that what passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human, at least as he conceptualizes it is probably to be unavoidably sentimental and naive and goo-prone and generally pathetic, is to be in some basic interior way forever infantile, some sort of not-quite-right-looking infant dragging itself anaclitically around the map, with big wet eyes and froggy-soft skin, huge skull, gooey drool. One of the really American things about Hal, probably, is the way he despises what it is he’s really lonely for: this hideous internal self, incontinent of sentiment and need, that pulses and writhes just under the hip empty mask, anhedonia.” Another name for that hip, cool mask is irony. (The worst thing about irony for me is that it attenuates emotion.)

When Bill W. meets his formerly alcoholic friend and asks him how he has obtained this new-found sobriety, the friend says point blank “I’ve got religion.” This is one solution that Bill W. had not seriously considered. Something innate in him resisted the idea of giving up control of his life to a higher power. But yet he is interested in any program that would lead to lasting sobriety. This paradox is the climax of Bill’s story, which feels somewhat postmodern (especially for a story published in 1939) because the complex solution to saving his life turns out to be relatively simple. The whole point of AA is the attempt to find this power greater than (and thus outside of) one’s self. Bill looks at his now-sober friend and admits “It began to look as though religious people were right after all. Here was something at work in a human heart which had done the impossible. My ideas about miracles were drastically revised right then.” What allows Bill W. to change his mind about “God” and religion and higher powers is the tacit permission to choose his own conception of God. When the grace is unshackled from dogma, it transforms him for good.

The challenge of AA is to get new members to accept this basic fact: they must give up control of their lives to a Higher Power. The challenge of writing fiction about human emotions is to get readers to identify and empathize with characters instead of just pitying them.

In a 2013 interview, George Saunders talked about some conversations he’d had with David Foster Wallace and other writers about this very subject.

[Saunders] described making trips to New York in the early days and having “three or four really intense afternoons and evenings with”, on separate occasions, Wallace and Franzen and Ben Marcus, talking to each of them about what the ultimate aspiration for fiction was. Saunders added: “The thing on the table was emotional fiction. How do we make it? How do we get there? Is there something yet to be discovered? These were about the possibly contrasting desire to: (1) write stories that had some sort of moral heft and/or were not just technical exercises or cerebral games; while (2) not being cheesy or sentimental or reactionary.” {emphasis added}

To empathize, one must truly see outside of one’s self. It is a process of forgetting the self. The “destruction of self-centeredness” is the price to be paid for sobriety, AA will tell you. Part of that involves a traditionally religious idea of servitude, sacrificing for others over and over, “in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.” The alternative is not just the default setting we are stuck with (or literal godlessness–the ultimate solitude), it is the modern and postmodern rat race, “the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.”

There is a myopic idea in the academic world of Wallace Studies that DFW & empathy has been “done.” Time to move along, now. Because they seem to lack sophistication and were covered early on, the recurring ideas of irony, sentimentality, and loneliness (or whatever) no longer hold appeal for the scholars who are, by the very nature of current scholarship, required to find some worthy topic that has been thus-far neglected. No one has written a dissertation on bird imagery in Wallace’s work so it’s suddenly “neglected” (for example) or maybe we do need more on Wallace’s work as it relates to race and gender and sexuality or analytic philosophy and political theory or any number of topics. But “empathy” was not just another topic Wallace was throwing out there for scholars to explore. This nexus of empathy-sentimentality-and “moral heft” gets to the DNA of who Wallace was as a writer and what he was hoping to accomplish in his art. Academics and critics can easily stand back and observe what it must take for a fictional character (which is basically what Wallace Himself is now anyway) to destroy “self-centeredness” but it is a uniquely human experience (rather than a purely cerebral one) for the realer, more enduring and sentimental part of one’s actual self to take charge and command that other part of the self to keep silent, “as if looking it levelly in the eye and saying, almost aloud, ‘Not another word.'”

To Toil and Not to Seek for Rest: Prayer in Infinite Jest

There are no atheists in halfway houses. Of course, they might enter the door as self-identified agnostics or nonbelievers, but to maintain a residence as part of a 12-step recovery program at such a halfway house they will be required to at least go through the motions. Rob mentioned that many, many of the earliest AA members butted up against this “higher power” requirement and declared that they were agnostics, too. AA, of course, butted right back and said Just Do It, Fake it Til You Make It, etc. And if you can’t fathom a higher power, AA itself can be your higher power. But here’s another barrier you might have: pray to this higher power. And this requirement might cause one to step back and contemplate just what is prayer, really?

“and when people with AA time strongly advise you to keep coming you nod robotically and keep coming, and you sweep floors and scrub out ashtrays and fill stained steel urns with hideous coffee, and you keep getting ritually down on your big knees every morning and night asking for help from a sky that still seems a burnished shield against all who would ask aid of it ” how can you pray to a ‘God’ you believe only morons believe in, still?”

At the end of his 1996 interview with David Foster Wallace, David Lipsky looks around Wallace’s house and sees a postcard tacked to the wall. That postcard contains the prayer of St. Ignatius.

Lord, teach me to be generous

To serve you as you deserve

To give and not to count the cost

To fight and not to heed the wounds

To toil and not to seek for rest

To labor and not ask for reward,

Save that of knowing that I do your will.

This is often called “St. Ignatius’s Prayer or the Prayer for Generosity. (BTW, Richard Powers wrote a book shortly after Wallace’s death called Generosity that includes a writing instructor who is losing is faith in writing. And Ignatius immediately calls to mind Ignatius J. Reilly, to me. There are a lot of parallels between Confederacy of Dunces and Infinite Jest, and of course John Kennedy Toole was a depressive who committed suicide at a young age.)

In Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, Lipsky says this reminds him of the AA prayer, which is also known as the Serenity Prayer. The Serenity Prayer is probably repeated at 99% of all AA meetings. However, there are some other AA/12-step prayers related to specific needs or steps.

http://www.12steps.org/12stephelp/prayers.htm

The full version of the Serenity Prayer, written by Reinhold Niebuhr goes like this:

God, give me grace to accept with serenity

the things that cannot be changed,

Courage to change the things

which should be changed,

and the Wisdom to distinguish

the one from the other.

Living one day at a time,

Enjoying one moment at a time,

Accepting hardship as a pathway to peace,

Taking, as Jesus did,

This sinful world as it is,

Not as I would have it,

Trusting that You will make all things right,

If I surrender to Your will,

So that I may be reasonably happy in this life,

And supremely happy with You forever in the next.

This longer version (which is not the one oft-repeated at AA) adds several AA concepts like accepting hardship, One Day at a Time, and surrendering the will as a requirement for reasonable happiness.

But in the halfway house, reasonable happiness is often far in the distance. An Ennet House resident drops in to Pat Montesian’s office and says “I’m awfully sorry to bother. I can come back. I was wondering if maybe there was any special Program prayer for when you want to hang yourself.”

Gately struggles, though not as fatalistically, with the prayer thing.

“He says when he tries to pray he gets this like image in his mind’s eye of the brainwaves or whatever of his prayers going out and out, with nothing to stop them, going, going, radiating out into like space and outliving him and still going and never hitting Anything out there, much less Something with an ear. Much much less Something with an ear that could possibly give a rat’s ass. He’s both pissed off and ashamed to be talking about this instead of how just completely good it is to just be getting through the day without ingesting a Substance, but there it is.”

Wallace works hard to convey exactly how AA works, and these moments of clarity or epiphany are the end results of that mysterious process, what is essentially a new form of belief. In a fantastic essay published in The Legacy of David Foster Wallace, Lee Konstantinou writes that “What Wallace wants is not so much a religious correction to secular skepticism allegedly run amok as new forms of belief—the adoption of a kind of religious vocabulary (God, prayer, etc.) emptied out of specific content, a vocabulary engineered to confront the possibly insuperable condition of postmodernity.” There is another post coming on that idea of “a vocabulary engineered to confront” but what rings true here is the way AA functioned (both in fiction and reality) as a new system of belief and a blueprint for life for Wallace.

Zadie Smith told us that “This was his literary preoccupation: the moment when the ego disappears and you’re able to offer up your love as a gift without expectation of reward. At this moment the gift hangs, like Federer’s brilliant serve, between the one who sends and the one who receives, and reveals itself as belonging to neither. We have almost no words for this experience of giving. The one we do have is hopelessly degraded through misuse. The word is prayer.”

Infinite Jest as Moral Novel

What is the point of life?

In this 1996 interview with Chris Lydon, Wallace says that somehow the present culture has taught us that “really the point of living is to get as much as you can and experience as much pleasure as you can and the implicit promise is that will make you happy.” That’s a sort of simplistic overview of the whole novel’s theme, but it fits with the ideas related to why alcohol and other pleasurable substances maybe don’t ultimately lead to happiness. So, if pleasure and entertainment are not at the core life’s purpose, what is? Or what should be?

The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous starts out by trying to convince you that you are an alcoholic. Pretty much every defense you can think of to rationalize getting drunk is refuted, or at least diffused, right up front. The idea of the responsible “gentleman drinker” whom every alcoholic aspires to be is debunked as myth right out of the gate. AA teaches you that the solution to stopping drinking is what we sometimes call “soul-searching” or what the Big Book sometimes calls being “properly armed with facts” about one’s self. This soul-searching leads to abandoning pride, a “confession of shortcomings” and the inevitable conclusion that the ability to stop drinking lies outside of one’s self.

Chapter 2 of the Big Book states the result of this soul-searching pretty starkly:

The great fact is just this, and nothing less: That we have had deep and effective spiritual experiences which have revolutionized our whole attitude toward life, toward our fellows and toward God’s universe. The central fact of our lives today is the absolute certainty that our Creator has entered into our hearts and lives in a way which is indeed miraculous. He has commenced to accomplish those things for us which we could never do by ourselves.

This is the organization that Ennet House requires its residents to attend every week. When life becomes impossible, they send you to AA.

In the book we are presented with many case studies of substance abuse, but the two most prominent are Don Gately and Hal Incandenza. One is forced into a halfway house after years of drugs and crime. The other is just starting to experience the spiritual side-effects of substances. We think of Hal as primarily a pot smoker, but he also drinks.

Hal’s mother, Mrs. Avril Incandenza, and her adoptive brother Dr. Charles Tavis, the current E.T.A. Headmaster, both know Hal drinks alcohol sometimes, like on weekend nights with Troeltsch or maybe Axford down the hill at clubs on Commonwealth Ave.; The Unexamined Life has its notorious Blind Bouncer night every Friday where they card you on the Honor System. Mrs. Avril Incandenza isn’t crazy about the idea of Hal drinking, mostly because of the way his father had drunk, when alive, and reportedly his father’s own father before him, in AZ and CA; but Hal’s academic precocity, and especially his late competitive success on the junior circuit, make it clear that he’s able to handle whatever modest amounts she’s pretty sure he consumes — there’s no way someone can seriously abuse a substance and perform at top scholarly and athletic levels, the E.T.A. psych-counselor Dr. Rusk assures her, especially the high-level-athletic part — and Avril feels it’s important that a concerned but un-smothering single parent know when to let go somewhat and let the two high-functioning of her three sons make their own possible mistakes and learn from their own valid experience, no matter how much the secret worry about mistakes tears her gizzard out, the mother’s.

Right here we are introduced to a family with a history of alcohol abuse (which ended in suicide for Hal’s father), a protective and worried mother, a private-school system that is so ingrained in equating success with the ability to “handle” substances that it tolerates a degree of underage drinking in the process. Wallace is quite clever in entertaining the reader (a blind bouncer!) as he doles out these diagnoses of systematic, societal-level problems that it lulls the reader into believing we are now insiders aware of all this modern-conundrum stuff too, but in the end don’t we want things to turn out well? Can’t we all just get along?

And Charles supports whatever personal decisions she [Avril] makes in conscience about her children. And God knows she’d rather have Hal having a few glasses of beer every so often than absorbing God alone knows what sort of esoteric designer compounds with reptilian Michael Pemulis and trail-of-slime-leaving James Struck, both of whom give Avril a howling case of the maternal fantods. And ultimately, she’s told Drs. Rusk and Tavis, she’d rather have Hal abide in the security of the knowledge that his mother trusts him, that she’s trusting and supportive and doesn’t judge or gizzard-tear or wring her fine hands over his having for instance a glass of Canadian ale with friends every now and again, and so works tremendously hard to hide her maternal dread of his possibly ever drinking like James himself or James’s father, all so that Hal might enjoy the security of feeling that he can be up-front with her about issues like drinking and not feel he has to hide anything from her under any circumstances.

What Avril values is this need for security and honesty when in fact her choices have created the exact opposite of her intentions. Hal is not open and honest with her about anything. He smokes pot in secret, addicted more to the solitude and self-punishment than the substance itself. He does not feel secure in the world or in his emotionally distant relationships.

The answers to the questions about how should one live are not answered explicitly in Infinite Jest, they are implied and inferred. The first step involves seeking meaning outside of one’s self, outside of the cage of one’s head. And at a very basic level, that’s the definition of religion.

The Big Book and Infinite Jest

In an interview, Cormac McCarthy famously said “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” Infinite Jest is no exception. The books that Wallace drew on for inspiration while constructing his novel include Don DeLillo’s End Zone, The Cinema Book, and many others. Perhaps the book least familiar to me but most familiar to Wallace and the most influential on Infinite Jest is the core text of Alcoholics Anonymous, titled simply The Big Book.

In conjunction with the 2016 Infinite Winter project, Rob Short and I will post here on various ways The Big Book, other AA literature, and AA in general helped shape Wallace’s fictional project. This issue also intersects with other major themes and topics at work in the novel, including the ideas of belief, faith, morality, and agnosticism so we will likely get into those issues, too.

This blog will not be “spoiler-free.” That’s probably not ideal for first-time readers of the novel. However, the book has been out for 20 years now and there is a sizable population of readers who have read the book or re-read the book several times.

I’ll let Rob write a formal introduction (if he chooses!) but you should know that he is a PhD candidate at the University of Florida, writing about David Foster Wallace. The work he has presented at the DFW conferences in Illinois is remarkable because it consistently breaks new scholarly ground, but is highly accessible (and relevant) to general readers. He and I have discussed these issues (about Wallace and AA and “worship”) privately for a while now, but I figured this is as good a time as any to invite others into the conversation and help us work out these ideas more publicly.

The Pynchon of Oklahoma

Desolation of Avenues Untold by Brandon Hobson

Civil Coping Mechanisms / $13.95 paper / 306 pages / August 25, 2015

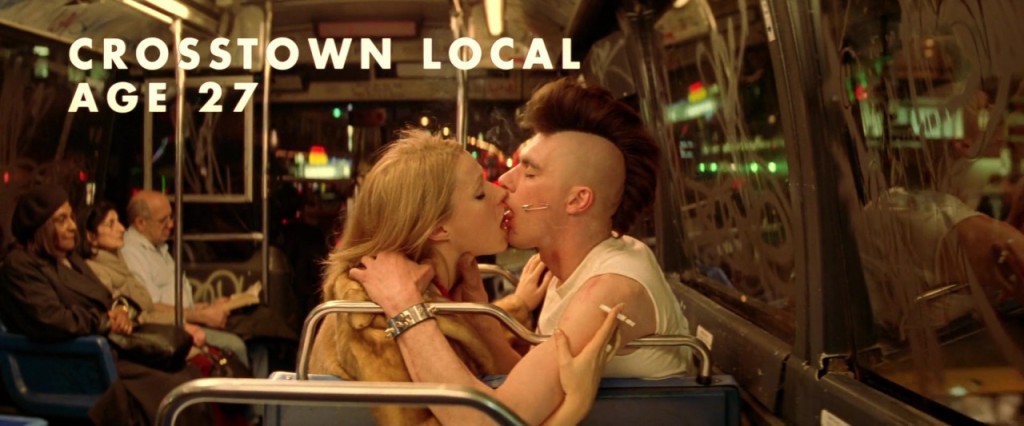

The lost sex tapes of an aging Charlie Chaplin occupy the secret center stage in this wild, neo-futuristic page-turner. Set mostly in Desolate City (D.C.), Texas, we meet Bornfeldt “Born” Chaplin, who surely must be related to The Tramp. Yet, his last name is merely a coincidence. The Tramp’s grandson turns out to be a former punk rocker (somewhat similar to Bucky Wunderlick) named Caspar Fixx.

Hobson, author of Deep Ellum, revels in pulling all the strands of this novel together and then letting them run loose and then pulling them back together again.

Hobson mixes in a framing device similar to Nabokov’s Lolita, a character named “Brandon Hobson,” and various other postmodern features that feel less like narrative tricks and more like comfortable gears for a writer at the top of his game. This is American fiction at its Ray-banned, smoke-blowing, cameras-are-rolling coolest.

Throughout the novel there are several nods to David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest: a lengthy filmography, scatological word play (Yushityu vs. Mishityu), and at the center of it all a riveting, cult film pursued by many. But, Hobson’s furious delight in naming characters, throwing them into surreal scenarios, and then expanding on the social problems of the day is less Wallace and DeLillo and more reminiscent of Pynchon in his heyday.

Another thing that separates Desolation from many other serious literary novels published these days is that it is actually fun to read. Just as one could picture Thomas Pynchon smirking when he wrote about erections, muted horns, Pig Bodine, and Doc Sportello, it’s easy to imagine Hobson taking utmost delight in creating Bleaker Street, naming a list of workshops available at a porn addiction conference, rolling a J, and listening to records with good old Dick Swaggert, professor of film studies at Thom Yorke College.

In the end, the question surrounding the hypothetical Chaplin sex tapes is one we must ask ourselves practically everyday now, a question about The Entertainment itself. With unfettered, instant access to pretty much every known human depravity, when a new spectacle or vice is revealed, when intense suffering can be passively consumed on a mobile screen, we must ask each other: Would you watch?

DFW Studies: Baudrillard Burn davidfosterwallace dfw DFWstudies Fogle InfiniteJest letters paleking ThePaleKing

by mattbucher

1 comment

A Few Trends in DFW Studies

There has been something like “David Foster Wallace studies” for a decade now, maybe longer. Stephen Burn’s reader’s guide to Infinite Jest was published in 2003. A Companion to David Foster Wallace Studies was published in 2013. The first academic conference on Wallace was held in Liverpool in 2009. The Second Annual David Foster Wallace Conference was held last week, in May 2015, at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois.

I didn’t get to attend half as many panels as I’d liked to, but I did get to read several other papers that I missed (in the past two years of conferences) after the fact and I noticed that there are some clear trends emerging in the scholarship, now in 2015. So what follows is just my own general impression of what people are doing at this point in time. It’s way more complicated and there are tons of mini-niches that I’m not even touching on here, but this is a broad-strokes overview of my own thoughts.

1. Fogle

My own paper at this year’s DFW Conference was about Section 22 of The Pale King (the story of Chris Fogle), so I was attuned to other mentions of Fogle’s story. In fact, there were at least two other papers that talked about Fogle’s conversion from a wastoid to a tax examiner. In previous years, I think it was Don Gately’s story that was used as the most common example of Wallace’s fictional project about redemption and adulthood. I was happy to see Fogle mentioned in so many places because I believe that section of The Pale King contains some of Wallace’s finest writing.

2. Baudrillard

Several papers talked at length about Baudrillard’s simulacra and the phases of the image. This is a rich subject for engaging much of the post-post-modern (or whatever) literature out there today and so it’s not too surprising that so many scholars have brought it to bear on Wallace’s work.

3. Theology/Religion

Wallace’s relationship to religion and the supernatural, both in his work and in his life as an artist, is fascinating because of how it evolves over time and how that belief or concept of the supernatural is reflected in his work. Current work in this area shows that theology / religion stands as a major element in Wallace’s fictional works.

4. The Letters

Stephen Burn’s keynote address at this year’s conference was centered around his effort to assemble a collection of Wallace’s letters on writing (rather than personal letters). Because of some difficulty securing permissions, it’s unclear when and if Burn’s manuscript will be published. It might take a couple of more years before we see this book, but it stands to be a major contribution to DFW studies. Burn separates out Wallace’s correspondence into three eras: The Apprentice Years, when DFW wrote to older masters; The Genius Years, when DFW wrote to contemporary writers; and the Emeritus Years, when DFW wrote to younger writers. The letters also reveal a lot about what Wallace was reading at each stage in his career.