InfiniteWinter: AA books davidfosterwallace dfw InfiniteJest

by mattbucher

2 comments

To Risk Sentimentality

“Sentimental” is one of the worst charges a critic can level at a book. Sometimes the insult is couched in “overly sentimental” or other adjectives and adverbs intended to soften the blow, but any novel that deals extensively with overt sadness or tenderness will likely have to weather such a criticism or work hard to preemptively avoid it. The challenge is for those novels to rebut the label of sentimentality by proving that they are in fact not exaggerating the magnitude of suffering or slipping off into the embarrassing territory of self-indulgent storytelling, but rather to risk seeming sentimental in order to emotionally connect with readers. I would argue that Infinite Jest succeeds in hoeing very close to the boundaries of sentimentality without stepping over them. Though Wallace stated in interviews that Infinite Jest was about “sadness” of some form or the other, that sadness is not existential, but is a symptom of some other, deeper problem.

The Big Book of AA doesn’t give a shit about sentimentality. It starts out with the surprisingly unsentimental and straightforward tale of the group’s founder, Bill W. His story is written in the first person and the story’s goals are not primarily literary, though it is laced through with supremely sophisticated rhetoric. Bill W. writes simple, declarative lines like: “I was very lonely and again turned to alcohol,” which intentionally don’t tug at heartstrings or exaggerate or euphemize what is the foundation of all AA rock-bottom stories. If you’ve read Infinite Jest and heard enough of these AA rock-bottom stories, then Bill W.’s story is what you might expect: here was a successful Wall Street banker and alcohol ruined his life. He compresses much of the story down and even skips over the worst of his binges with candid phrases like “drinking caught up with me again” or “I went on a prodigious bender.”

Bill W.’s story is so sad because of the prolonged period wherein he knows he must, absolutely must stop drinking and yet is unable to find the resolve to quit drinking on his own. This genuinely perplexes him. He desperately wants to quit drinking, but every hospital he tries only keeps him dry for a few weeks. When he gets home, every time, he says “the courage to do battle was not there.” Simple self-knowledge or awareness is not what saves him from an early grave. What saves him, in the end, is a chance meeting with an old friend—a former alcoholic who has found religion.

Bill W.’s story lacks the syrupy sentimentality we might expect because ultimately, like Infinite Jest, it is a story about personal enlightenment. Hal’s own path towards enlightenment involves wrestling his way out of the cage of loneliness: We enter a spiritual puberty where we snap to the fact that the great transcendent horror is loneliness, excluded encagement in the self. Once we’ve hit this age, we will now give or take anything, wear any mask, to fit, be part-of, not be Alone, we young. It is this very encagement that shoots down the very thought of sentimentality or engaging deeply with one’s own emotions in order to make peace with them. We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony at a young age where the face is fictile enough to assume the shape of whatever it wears. And then it’s stuck there, the weary cynicism that saves us from gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naiveté. Sentiment equals naiveté on this continent (at least since the Reconfiguration).

Part of what Wallace is arguing here is that there is no such thing as authentically transcending sentimentality. To do so only denies one’s self access to true humanity. “Hal, who’s empty but not dumb, theorizes privately that what passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human, at least as he conceptualizes it is probably to be unavoidably sentimental and naive and goo-prone and generally pathetic, is to be in some basic interior way forever infantile, some sort of not-quite-right-looking infant dragging itself anaclitically around the map, with big wet eyes and froggy-soft skin, huge skull, gooey drool. One of the really American things about Hal, probably, is the way he despises what it is he’s really lonely for: this hideous internal self, incontinent of sentiment and need, that pulses and writhes just under the hip empty mask, anhedonia.” Another name for that hip, cool mask is irony. (The worst thing about irony for me is that it attenuates emotion.)

When Bill W. meets his formerly alcoholic friend and asks him how he has obtained this new-found sobriety, the friend says point blank “I’ve got religion.” This is one solution that Bill W. had not seriously considered. Something innate in him resisted the idea of giving up control of his life to a higher power. But yet he is interested in any program that would lead to lasting sobriety. This paradox is the climax of Bill’s story, which feels somewhat postmodern (especially for a story published in 1939) because the complex solution to saving his life turns out to be relatively simple. The whole point of AA is the attempt to find this power greater than (and thus outside of) one’s self. Bill looks at his now-sober friend and admits “It began to look as though religious people were right after all. Here was something at work in a human heart which had done the impossible. My ideas about miracles were drastically revised right then.” What allows Bill W. to change his mind about “God” and religion and higher powers is the tacit permission to choose his own conception of God. When the grace is unshackled from dogma, it transforms him for good.

The challenge of AA is to get new members to accept this basic fact: they must give up control of their lives to a Higher Power. The challenge of writing fiction about human emotions is to get readers to identify and empathize with characters instead of just pitying them.

In a 2013 interview, George Saunders talked about some conversations he’d had with David Foster Wallace and other writers about this very subject.

[Saunders] described making trips to New York in the early days and having “three or four really intense afternoons and evenings with”, on separate occasions, Wallace and Franzen and Ben Marcus, talking to each of them about what the ultimate aspiration for fiction was. Saunders added: “The thing on the table was emotional fiction. How do we make it? How do we get there? Is there something yet to be discovered? These were about the possibly contrasting desire to: (1) write stories that had some sort of moral heft and/or were not just technical exercises or cerebral games; while (2) not being cheesy or sentimental or reactionary.” {emphasis added}

To empathize, one must truly see outside of one’s self. It is a process of forgetting the self. The “destruction of self-centeredness” is the price to be paid for sobriety, AA will tell you. Part of that involves a traditionally religious idea of servitude, sacrificing for others over and over, “in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.” The alternative is not just the default setting we are stuck with (or literal godlessness–the ultimate solitude), it is the modern and postmodern rat race, “the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.”

There is a myopic idea in the academic world of Wallace Studies that DFW & empathy has been “done.” Time to move along, now. Because they seem to lack sophistication and were covered early on, the recurring ideas of irony, sentimentality, and loneliness (or whatever) no longer hold appeal for the scholars who are, by the very nature of current scholarship, required to find some worthy topic that has been thus-far neglected. No one has written a dissertation on bird imagery in Wallace’s work so it’s suddenly “neglected” (for example) or maybe we do need more on Wallace’s work as it relates to race and gender and sexuality or analytic philosophy and political theory or any number of topics. But “empathy” was not just another topic Wallace was throwing out there for scholars to explore. This nexus of empathy-sentimentality-and “moral heft” gets to the DNA of who Wallace was as a writer and what he was hoping to accomplish in his art. Academics and critics can easily stand back and observe what it must take for a fictional character (which is basically what Wallace Himself is now anyway) to destroy “self-centeredness” but it is a uniquely human experience (rather than a purely cerebral one) for the realer, more enduring and sentimental part of one’s actual self to take charge and command that other part of the self to keep silent, “as if looking it levelly in the eye and saying, almost aloud, ‘Not another word.'”

Readers Anonymous: DFW’s Transformative Gifts and the Labor of Gratitude

What is it that compels thousands of strangers to organize themselves, both on the internet and in person, for the sole purpose of talking to each other about David Foster Wallace’s writing? With the exception of maybe Pynchon, I can’t think of another figure in contemporary American literature whose readers generate and engage in so much collaborative work.

By way of personal example, here’s a list of the Wallace projects I frequently consult for help with my writing or to clarify my thinking about DFW:

- Nick Maniatis’s thehowlingfantods.com

- The Wallace-l listerv

- Infinite Winter (website, subreddit, Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, Google+ if that’s your thing)

- Infinite Summer (same as above, plus its own 1,100-member forum)

- The Great Concavity Podcast

- Two Illinois State University Conferences (and a third this year)

- The Paris & London Conferences plus an upcoming Australian one

- Chris Ayers’ Poor Yorick Entertainment tumblr, “A Visual Exploration of the Filmography of James O. Incandenza“

- Text-specific wikis and utilities pages

The few times I’ve been lucky enough to make some small contribution to projects like these, I’ve always come away from the experience feeling like I’m running on rocket fuel. Collaborative work has the unique ability to remind me why it was that I started writing about Wallace in the first place. Whatever my level of participation, I always get back far more than what I put in.

But none of the items on this list would exist without the dedicated folks who maintain them and whose involvement far exceeds anything that could reasonably be called “participation.” Given the amount of labor required, what drives those who devote their time and energy to the creation and maintenance of projects like these? My palms start to sweat just thinking about the 17+ years of aggregate effort required to keep the lights on over at thehowlingfantods.com, to say nothing of the anxiety inherent in hosting an international conference (writing and distributing a CFP, reading and jurying submissions, sending out approval- and rejection notices, negotiating hotel group-rates, enduring headaches from the university’s legal department, catering meals, printing programs, talking down maniac academics in mid-freakout because their presentations’ AV-setups don’t work, and who-knows-what-else).

The only plausible theory for this kind of dedication to an author’s work I’ve come across (other than sheer psychosis) is Lewis Hyde’s conception of “gift economies,” which he outlines in his book The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World. Before I get into that, I should probably say here that the connection between Hyde & Wallace is interesting to me for a couple of reasons:

1) In the obligatory “Praise for” section of The Gift’s opening pages is a blurb from Wallace:

The Gift actually deserves the hyperbolic praise that in most blurbs is so empty. It is the sort of book that you remember where you were and even what you were wearing when you first picked it up. The sort that you hector friends about until they read it too. This is not just formulaic blurbspeak; it is the truth. No one who is invested in any kind of art, in questions of what real art does and doesn’t have to do with money, spirituality, ego, love, ugliness, sales, politics, morality, marketing, and whatever you call “value,” can readThe Gift and remain unchanged.

2) DFW’s copy of The Gift, now housed at UT Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, has Wallace’s annotations in it.

Hyde, who worked for several years as a counselor to alcoholics in the detoxification ward of a city hospital, presents the recovery program of Alcoholics Anonymous as a prime example of a “transformative gift,” one which must be offered without thought of return. In a footnote on page 74 (2006 ed.) Hyde reasons that for alcoholics, AA’s “gift” is a function of a the program’s (previously–mentioned) spiritual requirement, ”the belief in a higher power”:

Alcoholics who get sober in AA tend to become very attached to the group, at least to begin with. Their involvement seems, in part, a consequence of the fact that AA’s program is a gift. In the case of alcoholism, the attachment may be a necessary part of the healing process. Alcoholism is an affliction whose relief seems to require that the sufferer be bound up in something larger than the ego-of-one (in a “higher power,” be it only the power of the group). Hearings that call for differentiation, on the other hand, may be more aptly delivered through the market.(93 fn)

It’s a sort of hermeneutics of recovery: the only membership-requirement of Alcoholics Anonymous is “a desire to stop drinking,” which desire almost nobody truly has without hitting bottom. Time and again, AA’s official literature seems to go out of its way to remind newcomers that it’s only in the depths of such a low that most alcoholics are willing to submit to the rigors of the program. This receptiveness in the early days of AA’s program of recovery is doubly important because the next step after an honest and sincere desire to quit drinking is often the most difficult: the surrendering of will to a higher power. And here again, this may explain the pains taken by AA’s literature when it emphasizes over and over that this higher power can take whatever form a member chooses. In Infinite Jest, Wallace talks about this kind of hardcore receptiveness as the only real prerequisite for recovery:

The bitch of the thing is that you have to want to. If you don’t want to do as you’re told ”I mean as it’s suggested you do” it means that your own personal will is still in control[.] The will you call your own ceased to be yours as of who knows how many Substance-drenched years ago. […] This is why most people will Come In and Hang In only after their own entangled will has just about killed them. […] You have to want to take the suggestions, want to abide by the traditions of anonymity, humility, surrender to the Group conscience. If you don’t obey, nobody will kick you out. They won’t have to. You’ll end up kicking yourself out, if you steer by your own sick will. (357)

And in what seems to me a ridiculously convenient coincidence (in terms of the present argument), Hyde actually chooses AA as his analogue for explaining the circular nature of transformational gifts:

[M]ost artists are converted to art by art itself. The future artist finds himself or herself moved by a work of art, and, through that experience, comes to labor in the service of art until he can profess his own gifts. Those of us who do not become artists nonetheless attend to art in a similar spirit. We come to painting, to poetry, to the stage, hoping to revive the soul. And any artist whose work touches us earns our gratitude. […] for it is when art acts as an agent of transformation that we may correctly speak of it as a gift. A lively culture will have transformative gifts as a general feature“ it will have groups like AA which address specific problems, it will have methods of passing knowledge from old to young, it will have spiritual teachings available at all levels of maturation and for the birth of the spiritual self. (48)

To restate this passage for our purposes here: The best art is transformative for author and reader alike. Whether one is the giver or receiver of transformational art is merely a function of one’s position in the cycle. The transformational gift is passed freely from giver to recipient, who, transformed by gratitude, feels a duty to pass the gift on to the next recipient. This last step is the same gratitude-inspired service that AA’s 5th tradition and 12th step refer to: the transformational gift of AA, received by those able to “hang in there and keep coming back,” is that (as yet another AA maxim goes) “it works if you work it.” And this is where recovery’s hermeneutic process cycles back into itself: working the 12th step is the point at which the recipient, no longer a newcomer “having been transformed by AA’s gift” can assume the role of the giver by sponsoring new members. Here’s Wallace’s take on this cyclical process:

Giving It Away is a cardinal Boston AA principle. The term’s derived from an epigrammatic description of recovery in Boston AA: “You give it up to get it back to give it away.” Sobriety in Boston is regarded as less a gift than a sort of cosmic loan. You can’t pay the loan back, but you can pay it forward, by spreading the message that despite all appearances AA works, spreading this message to the next new guy who’s tottered in to a meeting and is sitting in the back row unable to hold his cup of coffee. (344)

Comparing that last quotation to Hyde’s description of the reciprocal relationship between gifts and gratitude, several parallels become apparent:

In each example I have offered of a transformative gift, if the teaching begins to “take,” the recipient feels gratitude. I would like to speak of gratitude as a labor undertaken by the soul to effect the transformation after a gift has been received. Between the time a gift comes to us and the time we pass it along, we suffer gratitude. Moreover, with gifts that are agents of change, it is only when we have come up to its level, as it were, that we can give it away again. Passing the gift along is the act of gratitude that finished the labor. The transformation is not accomplished until we have the power to give the gift on our own terms. Therefore, the end of the labor of gratitude is similarity with the gift or with its donor. Once this similarity has been achieved we may feel a lingering and generalized gratitude, but we won’t feel it with the urgency of true indebtedness. (48)

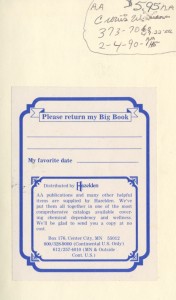

I can’t think of a better illustration of this labor of gratitude, gratitude for a gift of such immensity and meaning that it inspires the recipient’s own selfless giving than what you can find written on the flyleaves of the UF library’s copy of The Big Book:

One last thing: Hyde describes the gift-recipient’s “transformation” as one that produces a similarity with the gift or with its donor. As I re-read the AA sections of Infinite Jest, I can’t help but understand Wallace’s use of the word “identification” to mean anything other than this process of achieving similarity.In these sections of the novel, Wallace manages to show us precisely the part of recovery that Boston AA’s newcomers can’t see ”even though the gift’s transformation is already underway.”