To Toil and Not to Seek for Rest: Prayer in Infinite Jest

There are no atheists in halfway houses. Of course, they might enter the door as self-identified agnostics or nonbelievers, but to maintain a residence as part of a 12-step recovery program at such a halfway house they will be required to at least go through the motions. Rob mentioned that many, many of the earliest AA members butted up against this “higher power” requirement and declared that they were agnostics, too. AA, of course, butted right back and said Just Do It, Fake it Til You Make It, etc. And if you can’t fathom a higher power, AA itself can be your higher power. But here’s another barrier you might have: pray to this higher power. And this requirement might cause one to step back and contemplate just what is prayer, really?

“and when people with AA time strongly advise you to keep coming you nod robotically and keep coming, and you sweep floors and scrub out ashtrays and fill stained steel urns with hideous coffee, and you keep getting ritually down on your big knees every morning and night asking for help from a sky that still seems a burnished shield against all who would ask aid of it ” how can you pray to a ‘God’ you believe only morons believe in, still?”

At the end of his 1996 interview with David Foster Wallace, David Lipsky looks around Wallace’s house and sees a postcard tacked to the wall. That postcard contains the prayer of St. Ignatius.

Lord, teach me to be generous

To serve you as you deserve

To give and not to count the cost

To fight and not to heed the wounds

To toil and not to seek for rest

To labor and not ask for reward,

Save that of knowing that I do your will.

This is often called “St. Ignatius’s Prayer or the Prayer for Generosity. (BTW, Richard Powers wrote a book shortly after Wallace’s death called Generosity that includes a writing instructor who is losing is faith in writing. And Ignatius immediately calls to mind Ignatius J. Reilly, to me. There are a lot of parallels between Confederacy of Dunces and Infinite Jest, and of course John Kennedy Toole was a depressive who committed suicide at a young age.)

In Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, Lipsky says this reminds him of the AA prayer, which is also known as the Serenity Prayer. The Serenity Prayer is probably repeated at 99% of all AA meetings. However, there are some other AA/12-step prayers related to specific needs or steps.

http://www.12steps.org/12stephelp/prayers.htm

The full version of the Serenity Prayer, written by Reinhold Niebuhr goes like this:

God, give me grace to accept with serenity

the things that cannot be changed,

Courage to change the things

which should be changed,

and the Wisdom to distinguish

the one from the other.

Living one day at a time,

Enjoying one moment at a time,

Accepting hardship as a pathway to peace,

Taking, as Jesus did,

This sinful world as it is,

Not as I would have it,

Trusting that You will make all things right,

If I surrender to Your will,

So that I may be reasonably happy in this life,

And supremely happy with You forever in the next.

This longer version (which is not the one oft-repeated at AA) adds several AA concepts like accepting hardship, One Day at a Time, and surrendering the will as a requirement for reasonable happiness.

But in the halfway house, reasonable happiness is often far in the distance. An Ennet House resident drops in to Pat Montesian’s office and says “I’m awfully sorry to bother. I can come back. I was wondering if maybe there was any special Program prayer for when you want to hang yourself.”

Gately struggles, though not as fatalistically, with the prayer thing.

“He says when he tries to pray he gets this like image in his mind’s eye of the brainwaves or whatever of his prayers going out and out, with nothing to stop them, going, going, radiating out into like space and outliving him and still going and never hitting Anything out there, much less Something with an ear. Much much less Something with an ear that could possibly give a rat’s ass. He’s both pissed off and ashamed to be talking about this instead of how just completely good it is to just be getting through the day without ingesting a Substance, but there it is.”

Wallace works hard to convey exactly how AA works, and these moments of clarity or epiphany are the end results of that mysterious process, what is essentially a new form of belief. In a fantastic essay published in The Legacy of David Foster Wallace, Lee Konstantinou writes that “What Wallace wants is not so much a religious correction to secular skepticism allegedly run amok as new forms of belief—the adoption of a kind of religious vocabulary (God, prayer, etc.) emptied out of specific content, a vocabulary engineered to confront the possibly insuperable condition of postmodernity.” There is another post coming on that idea of “a vocabulary engineered to confront” but what rings true here is the way AA functioned (both in fiction and reality) as a new system of belief and a blueprint for life for Wallace.

Zadie Smith told us that “This was his literary preoccupation: the moment when the ego disappears and you’re able to offer up your love as a gift without expectation of reward. At this moment the gift hangs, like Federer’s brilliant serve, between the one who sends and the one who receives, and reveals itself as belonging to neither. We have almost no words for this experience of giving. The one we do have is hopelessly degraded through misuse. The word is prayer.”

Big Books and “Meaning as Use”

You see by this what I meant when I called pragmatism a mediator and reconciler and said that she “unstiffens” our theories. She has in fact no prejudices whatsoever, no obstructive dogmas, no rigid canons of what shall count as proof. She is completely genial. She will entertain any hypothesis, she will consider any evidence.

In short, she widens the field of search for God.

William James, Pragmatism

Since my last post, I’ve read (at least) two things that merit further consideration in this conversation about A.A. and Infinite Jest.

One has to do with Tom Bissell’s recent piece in the Times, which is apparently an excerpt from his introduction to the forthcoming 20th-anniversary edition of Wallace’s own Big Book. This part in particular elicited a reaction from one of my eyebrows:

“While I have never been able to get a handle on Wallace’s notion of spirituality, I think it is a mistake to view him as anything other than a religious writer. His religion, like many, was a religion of language.

I agree with Bissell that to understand Wallace (at least post-Jest Wallace) as anything other than a religious writer is a mistake—but only with the caveat that “religious” here means something very specific and non-doctrinaire. However, I’m confused by Tom Bissell’s confession of difficulty re: getting a handle on Wallace’s spirituality. Maybe this is some sort of rhetorical strategy on Bissell’s part; perhaps the introduction to an 1,100-page novel isn’t the place to launch into a paean to Alcoholics Anonymous. Alright, fine: it’s definitely not.

But if he truly means what he says that he “can’t get a handle on” Wallace’s notion of spirituality he must not have looked very hard. Wallace mentions spirituality and religion all over the place, from interviews with Brian Garner and Larry McCaffery, to the Kenyon speech, to nonfiction essays like “The Nature of the Fun,” to Infinite Jest itself. What’s more, Wallace is pretty consistent about what he says. And I’d argue this consistency stems from Wallace’s fidelity to (what I understand as) the source of his first serious engagements with religion: his participation in A.A.

But in typical Wallace fashion, he couldn’t just take what A.A. said about spirituality on faith; he had to do his own research. At least one of the texts Wallace consulted for this research was Huston Smith’s The World’s Religions: Our Great Wisdom Traditions (which by the time Wallace read it had been re-issued and re-titled; it was originally published as The Religions of Man).

Here’s a picture of the cover of the 1991 ed. like the one owned and annotated by Wallace, which copy is available for viewing at UT’s Harry Ransom Center:

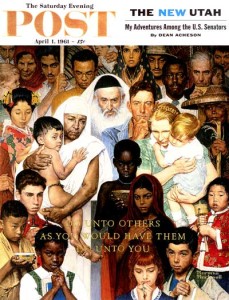

The cover image is a reproduction of a Norman Rockwell’s “Golden Rule,” a piece that first appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1961. (A mosaic version of the piece still hangs in the United Nations building in New York.) The text that sits on top of the image, Do unto others as you would have them do unto you is there in the original, as in Rockwell put it there.

I mention this here because I think it goes a long way toward helping us “get a handle on Wallace’s notion of spirituality.”

By way of evidence, here’s a photo of some of Wallace’s annotations in the Smith text, via (as ever!) Matt:

Here’s a transcription with Wallace’s underlining for clarity’s sake:

Might not becoming a part of a larger, more significant whole relieve life of its triviality? That question announces the birth of religion. For though in some watered-down sense there may be a religion of self-worship, true religion begins with the quest for meaning and value beyond self-centeredness. It renounces the ego’s claims to finality.

But what is this renunciation for? The question brings us to the two signposts on the Path of Renunciation. The first of these reads “the community,” as the obvious candidate for something greater than ourselves. In supporting at once our own life and the lives others, the community has an importance no single life can command. Let us, then, transfer our allegiance to it, giving its claims priority over our own.

This transfer marks the first great step in religion. It produces the religion of duty, after pleasure and success the third great aim of life in the Hindu outlook. Its power over the mature is tremendous. Myriads have transformed the will-to-get into the will-to-give, the will-to-win into the will-to-serve. Not to triumph but to do their best to acquit themselves responsibly, whatever the task at hand has become their prime objective.

And in the margin next to this underlining is Wallace’s note: AA.

I do not mean here to equate the underscoring of a passage with its unequivocal or uncritical endorsement. But neither do I think it a stretch to say that Wallace had read the A.A. literature closely enough to see in this passage from Smith the core principles of spirituality as they’re presented by Alcoholics Anonymous: the twin necessities of self-renunciation via the relinquishment of the will to a power greater than oneself, and the consequent undertaking of work in service of others. As The Big Book (cribbing KJV’s James 2) cautions: faith without works is dead.

The second thing that warrants mentioning: Anyone who’s read The Broom of the System knows how ham-fistedly Wittgenstein’s “meaning as use” maxim gets deployed in Wallace’s first novel. And I think one of the things that allowed Wallace to suspend his disbelief about the A.A.-mandated belief in a power greater than himself was the way the Big Book conceptualizes the notions of “meaning” and “use” as intrinsically bound up with one another. In the A.A. model, Wittgenstein’s aphorism is applied not just to language, but to the rather more immediate case of the recovering alcoholic struggling to cope with life after alcohol. In this context, asking “What’s the meaning of life?” is to ask “What is the use of my life?” or “Am I useful to others?”

This notion of “usefulness” and its relation to the “default-mode” of self-centeredness Wallace talks about in the commencement is one that crops up again and again in A.A.’s Big Book:

Never was I to pray for myself, except as my requests bore on my usefulness to others. Then only might I expect to receive. […]Simple, but not easy; a price had to be paid. It meant the destruction of self-centeredness (13-14).

In fact, the concept of service work, “passing it on,” as it is codified in one A.A. maxims is directly and repeatedly correlated with the chances of a successful recovery:

For if an alcoholic failed to perfect and enlarge his spiritual life through work and self-sacrifice for others, he could not survive the certain trials and low spots ahead. If he did not work, he would surely drink again, and if he drank he would surely die. Then faith would be dead indeed. With us it is just like that. […] Faith has to work twenty-four hours a day in and through us, or we perish (14-16); Our very lives, as ex-problem drinkers, depend upon our constant thought of others and how we may help meet their needs (20); Whatever our protestations, are not most of us concerned with ourselves, our resentments, or our self-pity? Selfishness, self-centeredness! That, we think, is the door of our troubles. [¦] So our troubles, we think, are basically of our own making. They arise out of ourselves, and the alcoholic is an extreme example of self-will run riot, though he usually doesn’t think so. Above everything, we alcoholics must be rid of this selfishness. We must, or it kills us! (BB 62).

Ultimately, the mere cessation of drinking is presented as not finally the point; it is rather a means to another rehabilitation; it is a restoration of the capacity for service:

At the moment we are trying to put our lives in order. But this is not an end in itself. Our real purpose is to fit ourselves to be of maximum service to God and the people about us (77).

The more connections I see between A.A. and David Foster Wallace, the more inclined I am to read the process of writing Infinite Jest as a function of “working the steps.” And if Wallace was sincere about working them, which I believe he was, this sincerity has a certain bearing on questions that get asked over and over about the novel.

In that often-cited interview I mentioned earlier, Wallace and McCaffery get to talking about form and contemporary American fiction. Wallace has, a couple of paragraphs back, just finished praising William Vollmann’s remarkable integrity because Vollmann doesn’t engage in formal extravagance or experimentation for its own sake. McCaffery follows up by asking about Wallace’s own experiments with form, to which Wallace gives his standard-issue response about the way Infinite Jest is structured–that certain formal choices in the novel (e.g. the endnotes) were made in order to solicit an amount of readerly work, and that this work is supposed to highlight the fact that IJ’s narrative is by its very nature a mediated thing. In other words, the formal features are there to encourage readers to understand themselves as participating in a conversation with the writer. McCaffery counters with a rather pointed question:

“LM: How is this insistence on mediation different from the kind of meta-strategies you yourself have attacked as preventing authors from being anything other than narcissistic or overly abstract or intellectual?

DFW: I guess I’d judge what I do by the same criterion I apply to the self-conscious elements you find in Vollmann’s fiction: do they serve a purpose beyond themselves?

I think that by Infinite Jest, Wallace has developed a writing ethic that is something like a pragmatic amalgam of Wittgenstein and A.A.’s notion of meaning-as-use. And I think it shows up in the writing, especially when comparing Wallace’s two novels. By Infinite Jest, the toll of Wallace’s personal experiences of addiction and recovery have changed what he lets himself get away with in his writing, theory- and form-wise.

And with regard to those changes, a final A.A. maxim seems apposite here, one that must have had a particularly dark inflection for Wallace: My best thinking got me here.

Infinite Jest as Moral Novel

What is the point of life?

In this 1996 interview with Chris Lydon, Wallace says that somehow the present culture has taught us that “really the point of living is to get as much as you can and experience as much pleasure as you can and the implicit promise is that will make you happy.” That’s a sort of simplistic overview of the whole novel’s theme, but it fits with the ideas related to why alcohol and other pleasurable substances maybe don’t ultimately lead to happiness. So, if pleasure and entertainment are not at the core life’s purpose, what is? Or what should be?

The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous starts out by trying to convince you that you are an alcoholic. Pretty much every defense you can think of to rationalize getting drunk is refuted, or at least diffused, right up front. The idea of the responsible “gentleman drinker” whom every alcoholic aspires to be is debunked as myth right out of the gate. AA teaches you that the solution to stopping drinking is what we sometimes call “soul-searching” or what the Big Book sometimes calls being “properly armed with facts” about one’s self. This soul-searching leads to abandoning pride, a “confession of shortcomings” and the inevitable conclusion that the ability to stop drinking lies outside of one’s self.

Chapter 2 of the Big Book states the result of this soul-searching pretty starkly:

The great fact is just this, and nothing less: That we have had deep and effective spiritual experiences which have revolutionized our whole attitude toward life, toward our fellows and toward God’s universe. The central fact of our lives today is the absolute certainty that our Creator has entered into our hearts and lives in a way which is indeed miraculous. He has commenced to accomplish those things for us which we could never do by ourselves.

This is the organization that Ennet House requires its residents to attend every week. When life becomes impossible, they send you to AA.

In the book we are presented with many case studies of substance abuse, but the two most prominent are Don Gately and Hal Incandenza. One is forced into a halfway house after years of drugs and crime. The other is just starting to experience the spiritual side-effects of substances. We think of Hal as primarily a pot smoker, but he also drinks.

Hal’s mother, Mrs. Avril Incandenza, and her adoptive brother Dr. Charles Tavis, the current E.T.A. Headmaster, both know Hal drinks alcohol sometimes, like on weekend nights with Troeltsch or maybe Axford down the hill at clubs on Commonwealth Ave.; The Unexamined Life has its notorious Blind Bouncer night every Friday where they card you on the Honor System. Mrs. Avril Incandenza isn’t crazy about the idea of Hal drinking, mostly because of the way his father had drunk, when alive, and reportedly his father’s own father before him, in AZ and CA; but Hal’s academic precocity, and especially his late competitive success on the junior circuit, make it clear that he’s able to handle whatever modest amounts she’s pretty sure he consumes — there’s no way someone can seriously abuse a substance and perform at top scholarly and athletic levels, the E.T.A. psych-counselor Dr. Rusk assures her, especially the high-level-athletic part — and Avril feels it’s important that a concerned but un-smothering single parent know when to let go somewhat and let the two high-functioning of her three sons make their own possible mistakes and learn from their own valid experience, no matter how much the secret worry about mistakes tears her gizzard out, the mother’s.

Right here we are introduced to a family with a history of alcohol abuse (which ended in suicide for Hal’s father), a protective and worried mother, a private-school system that is so ingrained in equating success with the ability to “handle” substances that it tolerates a degree of underage drinking in the process. Wallace is quite clever in entertaining the reader (a blind bouncer!) as he doles out these diagnoses of systematic, societal-level problems that it lulls the reader into believing we are now insiders aware of all this modern-conundrum stuff too, but in the end don’t we want things to turn out well? Can’t we all just get along?

And Charles supports whatever personal decisions she [Avril] makes in conscience about her children. And God knows she’d rather have Hal having a few glasses of beer every so often than absorbing God alone knows what sort of esoteric designer compounds with reptilian Michael Pemulis and trail-of-slime-leaving James Struck, both of whom give Avril a howling case of the maternal fantods. And ultimately, she’s told Drs. Rusk and Tavis, she’d rather have Hal abide in the security of the knowledge that his mother trusts him, that she’s trusting and supportive and doesn’t judge or gizzard-tear or wring her fine hands over his having for instance a glass of Canadian ale with friends every now and again, and so works tremendously hard to hide her maternal dread of his possibly ever drinking like James himself or James’s father, all so that Hal might enjoy the security of feeling that he can be up-front with her about issues like drinking and not feel he has to hide anything from her under any circumstances.

What Avril values is this need for security and honesty when in fact her choices have created the exact opposite of her intentions. Hal is not open and honest with her about anything. He smokes pot in secret, addicted more to the solitude and self-punishment than the substance itself. He does not feel secure in the world or in his emotionally distant relationships.

The answers to the questions about how should one live are not answered explicitly in Infinite Jest, they are implied and inferred. The first step involves seeking meaning outside of one’s self, outside of the cage of one’s head. And at a very basic level, that’s the definition of religion.