The Pynchon of Oklahoma

Desolation of Avenues Untold by Brandon Hobson

Civil Coping Mechanisms / $13.95 paper / 306 pages / August 25, 2015

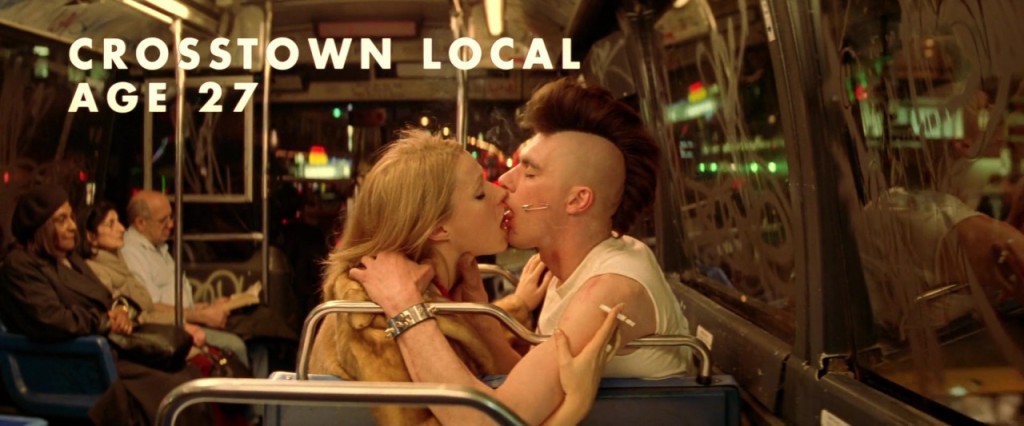

The lost sex tapes of an aging Charlie Chaplin occupy the secret center stage in this wild, neo-futuristic page-turner. Set mostly in Desolate City (D.C.), Texas, we meet Bornfeldt “Born” Chaplin, who surely must be related to The Tramp. Yet, his last name is merely a coincidence. The Tramp’s grandson turns out to be a former punk rocker (somewhat similar to Bucky Wunderlick) named Caspar Fixx.

Hobson, author of Deep Ellum, revels in pulling all the strands of this novel together and then letting them run loose and then pulling them back together again.

Hobson mixes in a framing device similar to Nabokov’s Lolita, a character named “Brandon Hobson,” and various other postmodern features that feel less like narrative tricks and more like comfortable gears for a writer at the top of his game. This is American fiction at its Ray-banned, smoke-blowing, cameras-are-rolling coolest.

Throughout the novel there are several nods to David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest: a lengthy filmography, scatological word play (Yushityu vs. Mishityu), and at the center of it all a riveting, cult film pursued by many. But, Hobson’s furious delight in naming characters, throwing them into surreal scenarios, and then expanding on the social problems of the day is less Wallace and DeLillo and more reminiscent of Pynchon in his heyday.

Another thing that separates Desolation from many other serious literary novels published these days is that it is actually fun to read. Just as one could picture Thomas Pynchon smirking when he wrote about erections, muted horns, Pig Bodine, and Doc Sportello, it’s easy to imagine Hobson taking utmost delight in creating Bleaker Street, naming a list of workshops available at a porn addiction conference, rolling a J, and listening to records with good old Dick Swaggert, professor of film studies at Thom Yorke College.

In the end, the question surrounding the hypothetical Chaplin sex tapes is one we must ask ourselves practically everyday now, a question about The Entertainment itself. With unfettered, instant access to pretty much every known human depravity, when a new spectacle or vice is revealed, when intense suffering can be passively consumed on a mobile screen, we must ask each other: Would you watch?

DFW Studies: Baudrillard Burn davidfosterwallace dfw DFWstudies Fogle InfiniteJest letters paleking ThePaleKing

by mattbucher

1 comment

A Few Trends in DFW Studies

There has been something like “David Foster Wallace studies” for a decade now, maybe longer. Stephen Burn’s reader’s guide to Infinite Jest was published in 2003. A Companion to David Foster Wallace Studies was published in 2013. The first academic conference on Wallace was held in Liverpool in 2009. The Second Annual David Foster Wallace Conference was held last week, in May 2015, at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois.

I didn’t get to attend half as many panels as I’d liked to, but I did get to read several other papers that I missed (in the past two years of conferences) after the fact and I noticed that there are some clear trends emerging in the scholarship, now in 2015. So what follows is just my own general impression of what people are doing at this point in time. It’s way more complicated and there are tons of mini-niches that I’m not even touching on here, but this is a broad-strokes overview of my own thoughts.

1. Fogle

My own paper at this year’s DFW Conference was about Section 22 of The Pale King (the story of Chris Fogle), so I was attuned to other mentions of Fogle’s story. In fact, there were at least two other papers that talked about Fogle’s conversion from a wastoid to a tax examiner. In previous years, I think it was Don Gately’s story that was used as the most common example of Wallace’s fictional project about redemption and adulthood. I was happy to see Fogle mentioned in so many places because I believe that section of The Pale King contains some of Wallace’s finest writing.

2. Baudrillard

Several papers talked at length about Baudrillard’s simulacra and the phases of the image. This is a rich subject for engaging much of the post-post-modern (or whatever) literature out there today and so it’s not too surprising that so many scholars have brought it to bear on Wallace’s work.

3. Theology/Religion

Wallace’s relationship to religion and the supernatural, both in his work and in his life as an artist, is fascinating because of how it evolves over time and how that belief or concept of the supernatural is reflected in his work. Current work in this area shows that theology / religion stands as a major element in Wallace’s fictional works.

4. The Letters

Stephen Burn’s keynote address at this year’s conference was centered around his effort to assemble a collection of Wallace’s letters on writing (rather than personal letters). Because of some difficulty securing permissions, it’s unclear when and if Burn’s manuscript will be published. It might take a couple of more years before we see this book, but it stands to be a major contribution to DFW studies. Burn separates out Wallace’s correspondence into three eras: The Apprentice Years, when DFW wrote to older masters; The Genius Years, when DFW wrote to contemporary writers; and the Emeritus Years, when DFW wrote to younger writers. The letters also reveal a lot about what Wallace was reading at each stage in his career.